What I Did Not Learn About Writing In School

At the start of the year, I decided to write more consistently and figured I might as well get better at it. Thus, I compiled a writing curriculum and studied some of the best books, essays, and videos on writing non-fiction.

I was surprised how much I didn’t learn about writing (at school). No, I’m not talking about grammar, punctuation, or essay structure. I’m talking about how to write for a wider audience, at a regular pace.

Here, I’ll share some of the uncommon and best advice I’ve come across. You won’t just be hearing from me—I’ve included many quotes from great thinkers, writers, and authors who have mastered the craft of writing. Whether you’re just starting to write or an old hand, I hope this will be helpful to you.

Writing is 80% preparation, 20% writing

In school, my writing was assessed by picking a topic (out of twelve) and pounding out an essay in 90 minutes. No research, little time for organizing thoughts, starting with a blank sheet of paper. Thus, I thought that to write, we just… wrote.

Now, I realize that the bulk of the work starts before the act of writing.

It starts when we read good books and articles, have great conversations, and experience the world. It continues when we note down what is useful for our work and writing, and make connections between them. And when we are ready to write, most of the legwork has already been done; we can focus on weaving it into a coherent, succinct essay.

But don’t just take my word for it. Here’s Roy Peter Clark, author of “Writing Tools”, on preparation:

“Good writers prepare for the next writing project, even if it is not yet on the radar screen. … As soon as I declare my interest in an important topic, a number of things happen. I notice more things about my topic.

Item by item, anecdote by anecdote, statistic by statistic, your boxes of curiosity fill up without much effort, creating a literary life cycle: planting, cultivation, and harvesting.”

And here’s Nick Maggiulli (Of Dollars and Data), sharing about his writing process, during a recent chat with David Perell:

“I consume information, think, and write. I would say I spend about 80% of my time consuming and thinking, and only 20% of my time writing.”

Nick then showed his drafts, of which he has multiple at any one time. In one draft, he collected anecdotes, quotes (by Michelle Obama and Jack Bogle), and charts. They were all there, ready to be organised and spun into an essay.

Preparation was also how German sociologist Niklas Luhmann published more than 70 books and 500 scholarly articles. He credits his work to his Zettelkasten (German for “slip box”), which grew to a collection of 90,000 notes, all handwritten on index cards.

Writing is hard for everyone

Early on, I got the impression that writing was supposed to be easy. I studied with geniuses and maestros who wrote beautiful essays during exams. Little did I know that they memorized paragraphs which could be plug-and-played.

Once I accepted that writing was difficult, I had less self-doubt and criticism. And without my biggest critic (me) interfering, writing became more enjoyable (though no less difficult). I also took comfort when I realized that the writing masters also had similar struggles with writing:

Here’s William Zinsser, author of “On Writing Well”, sharing his experience:

“What was it like to be a writer? (I was asked) … I said that writing wasn’t easy and wasn’t fun. It was hard and lonely, and the words seldom just flowed.

Writing is hard work. A clear sentence is no accident. Very few sentences come out right the first time, or even the third time. Remember this in moments of despair. If you find that writing is hard, it’s because it is hard.”

And here’s Stephen King, sharing about the rejection of his writing, in “A Memoir on Writing”:

“When I got the rejection slip, I pounded a nail into the wall … and poked it into the wall. … By the time I was fourteen, … the nail in my wall would no longer support the weight of the rejection slips impaled upon it.”

You don’t find your niche; your niche finds you

In school, we would pick a topic, thesis or question, then submit a paper at the end of the term. While it’s (relatively) easy to decide on a topic for a single essay, picking a theme to write about regularly can be paralyzing. It’s no wonder writers are often asked: “How did you figure out what to write about?”

I was surprised to learn that they didn’t start writing with any topics in mind. They just wrote a piece on something they found interesting. Then another. And another. After a year or three, themes and topics and niches emerged from their work.

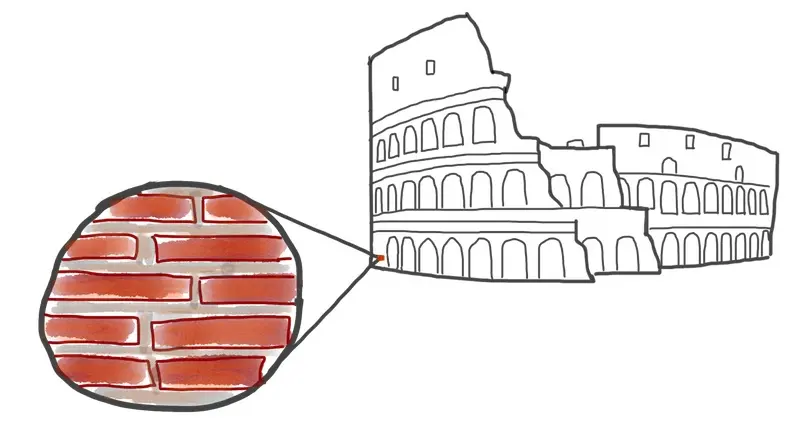

Don't worry too much about each individual essay. Brick by brick, your body of work will appear.

Here’s Dan Shipper, of Superorganizers, sharing advice on deciding what to write about—don’t overthink it, just write.

“Saying that I need to find the thing that I will do and write about for many years is kinda the wrong way to think about it. It puts too much pressure on writing and working on stuff that you end up being: ‘Oh, it’s too hard.’

Think of just writing one article, and don’t worry about the rest. And then write another one. Over time, something that is organic, and makes sense looking backwards, is going to emerge.

People get tripped up thinking they have to identify these big parts about their personality and write about them and the thing that makes them most unique. Just writing and shipping consistently is going to be the thing that helps you discover that—there’s no substitute for this.”

In the same podcast, Nathan Baschez, of Divinations, agreed and suggests not to bother too much about your topics.

“Totally agree. It helps to have some label, but don’t worry too much about it as you can always change it. And the definition of what fits in this can expand.”

Similarly, Patrick McKenzie (@patio11) wrote about various topics for several years before finally figuring out his niche.

“For several years, I just decided to write whatever was on my mind that day. If I did a lot of accounting, I would write about it. If I did optimization on my Java Swing app, I would write about it. It was very scattershot.

After a couple of years, … I realised that I wrote about the intersection of marketing and engineering very well. The more I wrote about things in that intersection, the better it did. And the more I wrote long, meaty, detail-heavy posts, the better they did.

So I started focusing on this. … People started liking the output more. And I started getting better at that variety of output. This led to a virtuous cycle.”

Your writing is nothing if not useful

In school, we always had one—and only one—reader (who read for the sole purpose of grading us). Thus, we focused on grammar, organization, clarity, and persuasiveness. We were less concerned about writing to connect with readers, to provide value.

In some cases, academic careers are affected, where papers perceived as useless don’t get published. It can also hinder your goals and work, where emails, proposals, and documents with no perceived value are not read.

Here’s what Larry McEnerney, the Chicago hard-ass cop of writing had to say about value:

“Yes, your writing needs to be clear, organised, persuasive. But more than anything else, your writing needs to be valuable. Because if it’s not that, nothing else matters. If it’s clear and useless, it’s useless. If it’s organised and useless, it’s useless. If it’s persuasive and useless, it’s useless.

Value is determined by the community—this is why writing is about readers, and not about content. Value lies in readers, not in the writing.”

Paul Graham devoted an entire essay on how to write usefully:

“What should an essay be? Many people would say persuasive. That’s what a lot of us were taught essays should be. But I think we can aim for something more ambitious: that an essay should be useful.

Useful writing tells people something true and important that they didn’t already know, and tells them as unequivocally as possible.”

Your voice is not how you write; your voice is you

When I started writing, I often wondered about my style, my “voice”. What is my voice and how should I speak to the reader?

I’ve come to the conclusion that voice has little to do with writing. Instead, it comes from character and personality. How we are as a person, that’s the style and voice that will come across in our writing. It’s not something I should focus too much on.

Here’s Strunk and White on style:

“Young writers often suppose that style is garnish for the meat of prose, a sauce by which a dull dish is made palatable. Style has no such separate entity; it is nondetachable, unfilterable.

The beginner should approach style warily, realising that it is an expression of self, and should resolutely turn away from all devices that are popularly beloved to indicated style—all mannerisms, tricks, adornments. The approach to style is by way of plainness, simplicity, orderliness, sincerity.”

And here’s William Zinsser again, this time on the topic of voice:

“I wrote one book about baseball and one about jazz. … I tried to write them both in … my usual style, though the books were widely different in subject … Don’t alter your voice to fit your subject. Develop one voice that readers will recognise when they hear it on the page.

When we say we like the style of certain writers, what we mean is that we like their personality as they express on paper.”

And here’s Paul Graham’s suggestion on how to speak to the reader through writing:

“Something comes over most people when they start writing. They write in a different language than they’d use if they were talking to a friend.

Perhaps the best solution is to write your first draft the way you usually would, then afterward look at each sentence and ask ‘Is this the way I’d say this if I were talking to a friend?’ If it isn’t, imagine what you would say, and use that instead.”

Conclusion

Writing is difficult. Getting better takes time. Finding your niche takes time. Research, connecting the dots, writing, rewriting (and rewriting again) takes time. Be patient with yourself. Enjoy the entire process.

If you’re thinking of starting, start. Just write one piece. It can be about anything, as long as you’re interested in it. It doesn’t have to be good or perfect. But you have to start.

What else have you learnt about writing that surprised you? Let me know by replying to this tweet or in the comments below.

Early this year, I compiled a curriculum of the best books, essays, and videos on writing non-fiction.

— Eugene Yan (@eugeneyan) August 4, 2020

I was surprised by how much I didn't learn about writing in school.

Here are some of the uncommon and best advice I've come across (a thread👇).https://t.co/RUmlu0nmjD

My writing curriculum (suggestions welcome!)

Books

- The Elements of Style (William Strunk Jr. & E. B. White)

- On Writing Well (William Zinsser)

- Writing Tools (Roy Peter Clark)

- A Memoir of the Craft: On Writing (Stephen King)

- How to Take Smart Notes (Sönke Ahrens)

- Writing Well: How to write purposefully (Julian Shapiro)

Essays

- Writing, Briefly (Paul Graham)

- How to Write Usefully (Paul Graham)

- Write Like You Talk (Paul Graham)

Videos

- The Craft of Writing Effectively (Larry McEnerney)

- How To Build A Popular Newsletter In 6 Months (Nathan Baschez & Dan Shipper)

- How to Grow Your Business by Writing (Sahil Lavingia & David Perell)

- Why You Should Become Internet Famous (Patrick McKenzie & David Perell)

- How to Write Weekly and Accelerate Your Career (Nick Maggiulli & David Perell)

Thanks to Yang Xinyi, Gian Segato, Padmini Pyapali, Michael Shafer, and Joel Christiansen for reading drafts of this.

If you found this useful, please cite this write-up as:

Yan, Ziyou. (Aug 2020). What I Did Not Learn About Writing In School. eugeneyan.com. https://eugeneyan.com/writing/what-i-did-not-learn-about-writing-in-school/.

or

@article{yan2020school,

title = {What I Did Not Learn About Writing In School},

author = {Yan, Ziyou},

journal = {eugeneyan.com},

year = {2020},

month = {Aug},

url = {https://eugeneyan.com/writing/what-i-did-not-learn-about-writing-in-school/}

}Share on:

Browse related tags: [ learning writing 🩷 ] or

Join 11,100+ readers getting updates on machine learning, RecSys, LLMs, and engineering.