Stop Taking Regular Notes; Use a Zettelkasten Instead

In the previous post, I shared about reading -> note-taking -> writing. Note-taking is a key step that converts what you read and learn into writing. This post expands on note-taking.

What’s wrong with regular note-taking?

From personal experience, regular note-taking doesn’t work.

Okay, that’s a sweeping statement. To some extent, it does. Scribbling on the margins is helpful for quickly recording insights and ideas that come while reading. Making summaries of books, articles, and papers help distil the gist and review the knowledge in future. Highlighting is… nope, highlighting doesn’t work—it’s just too passive.

Why do I say regular note-taking doesn’t work then?

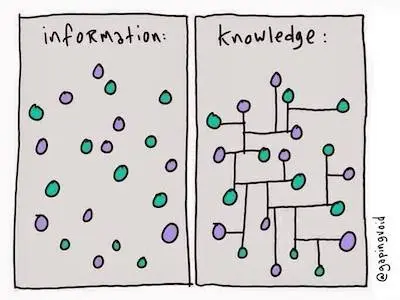

Because the notes stay as separate notes. Ideas and knowledge remains scattered as individual pieces. In regular note-taking, connections between ideas are not made by default. When reviewing a note, other relevant notes (i.e., ideas) don’t present themselves. If your notes are digital, you might do a free-text search. If not, you might flip through your notebooks, or worse, not bother.

Information vs. Knowledge (by @gapingvoid)

I didn’t realise this was an issue until I stumbled upon the Zettelkasten, which emphasizes building connections between notes.

What is a Zettelkasten?

Zettelkasten is German for “slip-box”. It originates from German sociologist Niklas Luhmann.

One thing you should know about Luhmann—he was extremely productive. In his 40 years of research, he published more than 70 books and 500 scholarly articles.

How did he do accomplish this? He credits it to his Zettelkasten which focuses on connections between notes. He realised early that a note is only useful in its context, specifically, the other notes it is related to.

Here’s how a Zettelkasten works:

- Write each idea you come across on a card.

- Link idea cards to other relevant idea cards (idea -> idea link).

- Sort cards into broader topic boxes (idea -> topic link).

This is oversimplifying it, but I hope you get the gist. The key is to make connections between ideas during note-taking, way before you need to review them for your work. This forces you to actively connect the dots (during note-taking) and lets you find relevant ideas with ease in future.

Luhmann built a massive Zettelkasten of 90,000 notes with handwritten index cards and a wooden cabinet. Thankfully, we have digital alternatives that make it easier to navigate (and read otherwise illegible handwriting).

Niklas Luhmann's index cards

(There are many good articles on Luhmann, his Zettelkasten, and how he used it; I’ve listed some for further reading at the end of this post.)

How to implement your digital Zettelkasten

Some free, digital Zettelkastens include zettelkasten.de, zettlr, and roamresearch. I use Roam. It has a minimal set of features required for my workflow and is actively being developed and improved on by Conor White-Sullivan.

Here’s my note-taking approach based on the Zettelkasten and Roam. I made tweaks to keep the process lightweight and thus easier to maintain as a habit.

Literature note

Every (useful) book, article, or paper I read is added as a literature note. Each literature note has the following metadata: (i) tag for #literature note, (ii) source (e.g., book title, URL), and (iii) author.

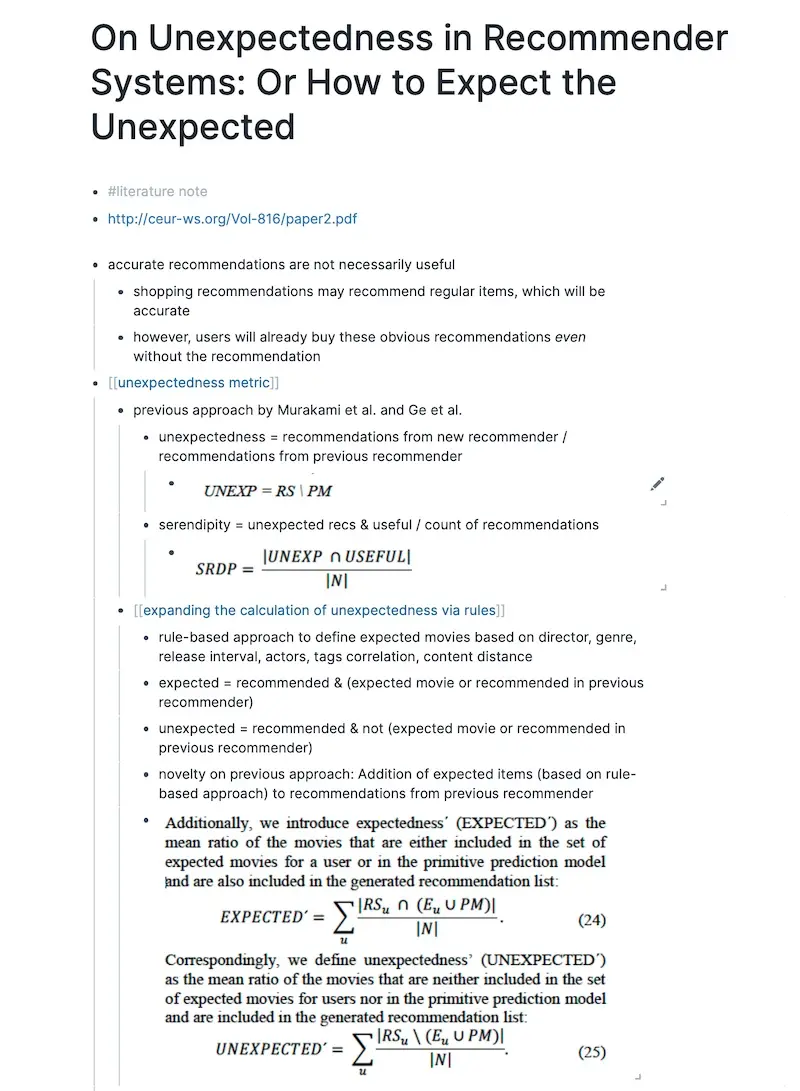

Then, I summarise the content as how I usually would, condensing each key idea as a simple sentence, in my own words. (This sentence will be converted to a permanent note later.) Then, I elaborate on this key idea with a few bullet points. Here’s how a sample literature note looks like.

Metadata in the first two bullet points with content right after

Permanent note

Some key ideas in a literature note are converted into a permanent note (hey, not all ideas are useful, right?) How do I choose what to make a permanent note? There are two general criteria:

- Is this an idea I would explore further and apply in my work/writing? Or;

- Is this an idea I can connect to other relevant ideas in my Zettelkasten?

Making a permanent note is easy in Roam—just wrap the sentence in [[ ]] brackets. Permanent notes have slightly more metadata:

- Tag for

#permanent note. - Topic tags such as

#machine learning,#recsys. - Source, which is just a link to the literature note.

- Relevant permanent notes and a short explanation of how it is relevant.

- Summary of the idea in prose.

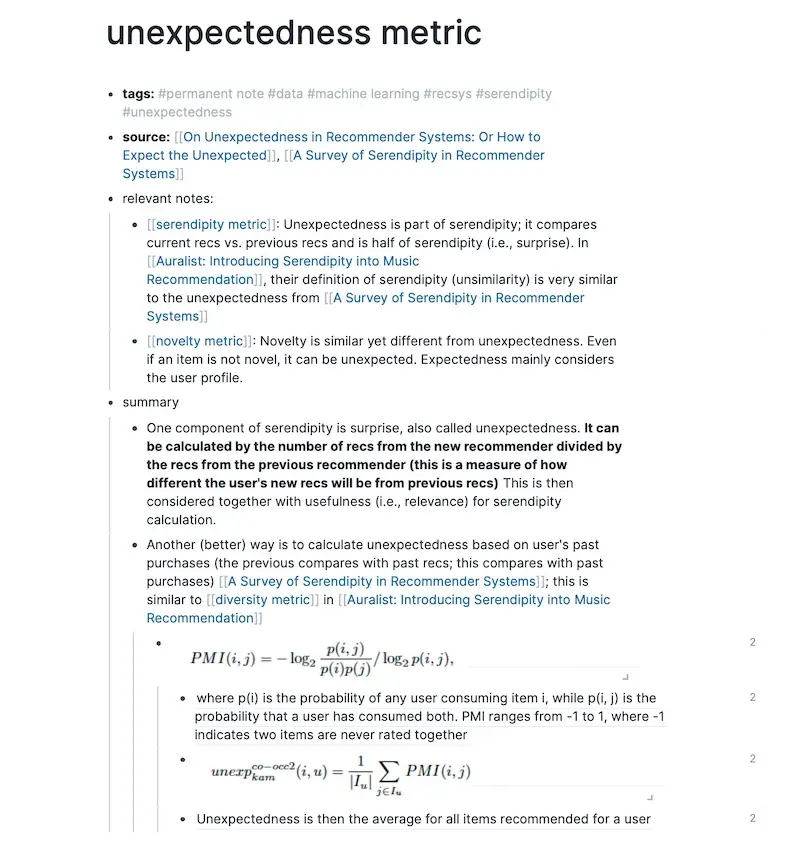

Here’s how a permanent note looks like. It is based on the previous literature note.

Connections made via relevant notes and #topic tags

Writing a permanent note takes effort. More effort than say… highlighting. You need to make connections with other notes and explain how they are related. You need to summarise the idea and knowledge in your own words, ensuring you really understood.

But putting in the effort upfront, during note-taking, makes it significantly easier to review and use your notes to synthesize content when writing.

Topics

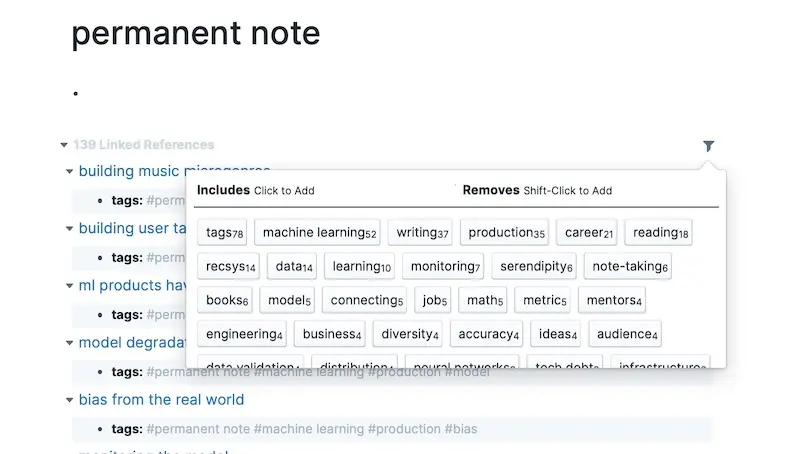

If you diligently added #topic tags, this is already done. Topic tags make navigating permanent notes easy in Roam. Clicking on #permanent note presents all permanent notes. You can then filter with #topic tags.

Here’s an example of my #permanent notes and some tags it has.

It's easy to see what you've been focusing on

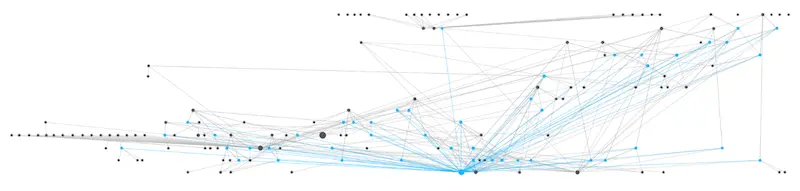

After a few weeks, here’s how the graph of my Zettelkasten notes looks like. The biggest blue dot close to the bottom centre is the #permanent note node. I find watching how this knowledge graph grows satisfying. You can track how your knowledge, and the connections between them, grows.

This is not an artificial neural network

Further reading on how to use Roam for note-taking is included at the end of this post. Shu Omi’s short, hands-on video is highly recommended.

Conclusion

Though it’s still early days, adopting a Zettelkasten has been one of my most productive habits. Writing the previous post was easier by consulting my notes on topics for #reading, #note-taking, #writing, and #learning. Finding related notes was also much simpler.

Further reading

- How to take smart notes

- Summary of “How to Take Smart Notes”

- More on Luhmann and his Zettelkasten

- Shu Omi’s Zettelkasten in Roam (video)

- Nat Eliason has a similar approach, if you prefer writing to video

- Anne Laure has a slightly different approach that you may find interesting

- Luhmann’s work

If you found this post useful, share this tweet with your friends. Help them write more useful notes. =)

Regular note-taking didn't work for me.

— Eugene Yan (@eugeneyan) May 10, 2020

Notes stay separate—connections are not made.

I fixed this by building a Zettelkasten using @RoamResearch.

(Zettelkasten originates from highly prolific sociologist Niklas Luhmann. He wrote 70 books & 500 scholarly articles.)

Thread 👇 pic.twitter.com/exVfl5EYXT

Update: Wow this really blew up on Hacker News (>600 points).

If you found this useful, please cite this write-up as:

Yan, Ziyou. (Apr 2020). Stop Taking Regular Notes; Use a Zettelkasten Instead. eugeneyan.com. https://eugeneyan.com/writing/note-taking-zettelkasten/.

or

@article{yan2020zettelkasten,

title = {Stop Taking Regular Notes; Use a Zettelkasten Instead},

author = {Yan, Ziyou},

journal = {eugeneyan.com},

year = {2020},

month = {Apr},

url = {https://eugeneyan.com/writing/note-taking-zettelkasten/}

}Share on:

Browse related tags: [ writing learning productivity 🔥 ] or

Join 11,100+ readers getting updates on machine learning, RecSys, LLMs, and engineering.