Improving Recommendation Systems & Search in the Age of LLMs

Recommendation systems and search have historically drawn inspiration from language modeling. For example, the adoption of Word2vec to learn item embeddings (for embedding-based retrieval), and using GRUs, Transformer, and BERT to predict the next best item (for ranking). The current paradigm of large language models is no different.

Here, we’ll discuss how industrial search and recommendation systems have evolved over the past year or so and cover model architectures, data generation, training paradigms, and unified frameworks:

- LLM/multimodality-augmented model architecture

- LLM-assisted data generation and analysis

- Scaling Laws, transfer learning, distillation, LoRAs, etc.

- Unified architectures for search and recommendations

LLM/multimodality-augmented model architecture

Recommendation models are increasingly adopting language models and multimodal content to overcome traditional limitations of ID-based approaches. These hybrid architectures include content understanding alongside the strengths of behavioral modeling, addressing the common challenges of cold-start and long-tail item recommendations.

Semantic IDs (YouTube) explores content-derived features as substitutes for traditional hash-based IDs. This approach targets difficulties in predicting user preferences for new and infrequently interacted items. Their solution involves a two-stage framework.

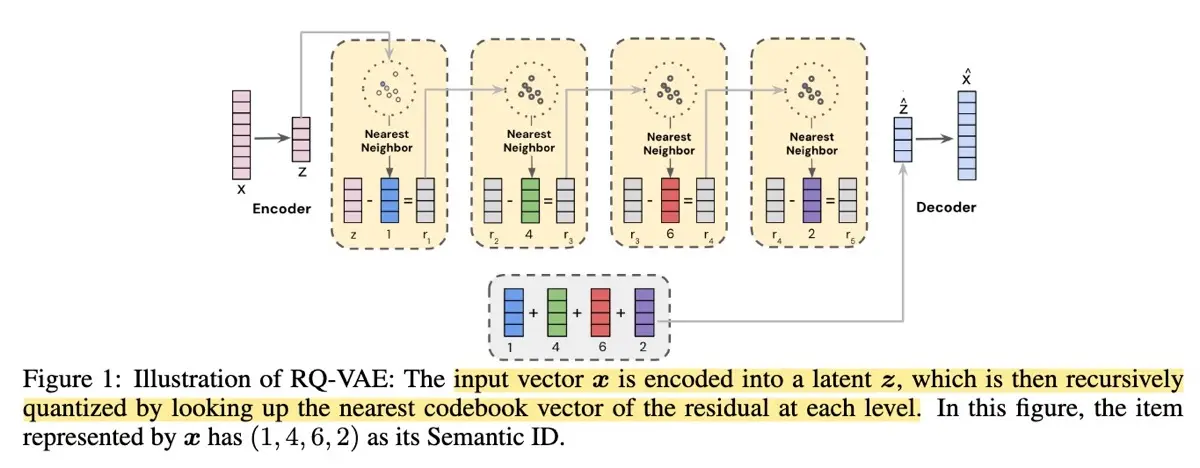

In the first stage, a transformer-based video encoder (similar to Video-BERT) generates dense content embeddings. These embeddings are then compressed into discrete Semantic IDs through a Residual Quantization Variational AutoEncoder (RQ-VAE). Representing user histories with these compact semantic IDs—a few integers rather than high-dimensional embeddings—significantly improves efficiency. Once trained, the RQ-VAE is frozen and used to generate Semantic IDs for the second stage to train a production-scale ranking model.

The RQ-VAE itself is a single-layer encoder-decoder structure with a 256-dimensional latent space. It has eight quantization levels with a codebook of 2048 entries per level. The encoder maps content embeddings to a latent vector, while a residual quantizer discretizes this vector, and the decoder reconstructs the original embedding. The initial embeddings originate from a transformer with a VideoBERT backbone, producing detailed, 2048-dimensional representations that capture the topical content in video.

To integrate Semantic IDs into ranking models, the authors propose two techniques: an N-gram-based approach, which groups fixed-length sequences, and a SentencePiece Model (SPM)-based method that adaptively learns variable-length subwords. The ranking model is a multi-task production ranking model that recommends the next video to watch given the current video and user history.

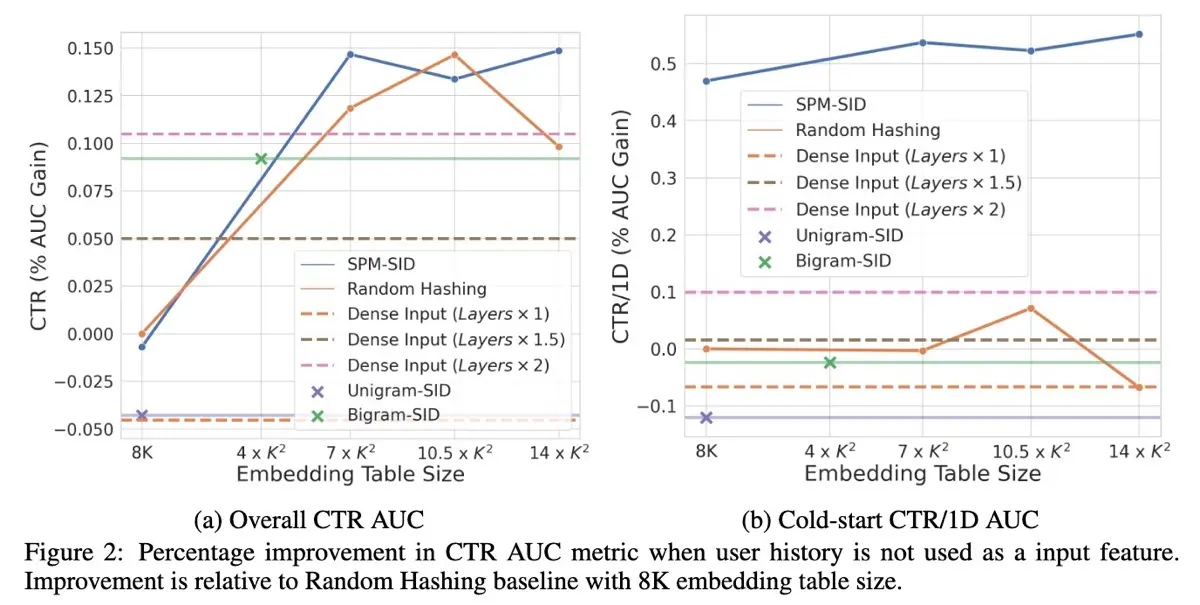

Results: Directly using the dense content embeddings performed worse than using random hash IDs. The authors hypothesize that ranking models heavily rely on memorization from the ID-based embedding tables—replacing these with fixed dense content embeddings led to poorer CTR. However, both N-gram and SPM methods did better than random hashing, especially in cold-start scenarios. Ablation tests revealed that while N-gram approaches had a slight advantage when embedding table sizes were limited (e.g., $8 \times K$ or $4 \times K^2$), SPM methods offered superior generalization and efficiency with larger embedding tables.

Dense content embeddings (dashed lines) perform worse than random hashing (solid orange).

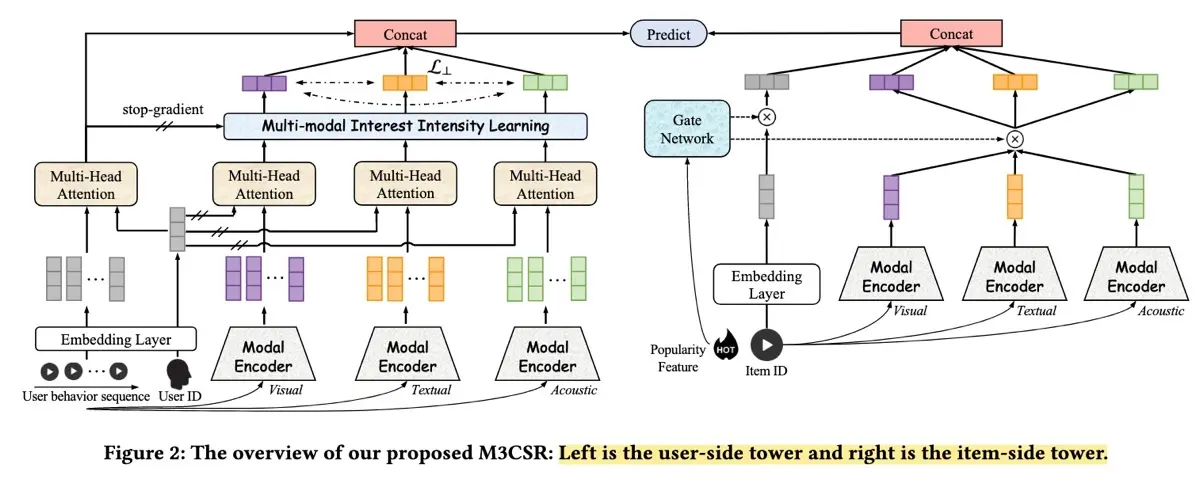

Similarly, M3CSR (Kuaishou) introduces multimodal content embeddings (visual, textual, audio) clustered via K-means into trainable category IDs. This transforms static content embeddings into adaptable, behavior-aligned representations.

The M3CSR framework has a dual-tower architecture, splitting user-side and item-side towers to optimize for online inference efficiency where user and item embeddings can be pre-computed and indexed via approximate nearest neighbor indices. Item embeddings are derived from multimodal pretrained models—ResNet for visual, Sentence-BERT for text, and VGGish for audio—and concatenated into a single embedding vector. These vectors are then clustered using K-means (with approximately 1,000 clusters from over 10 million videos).

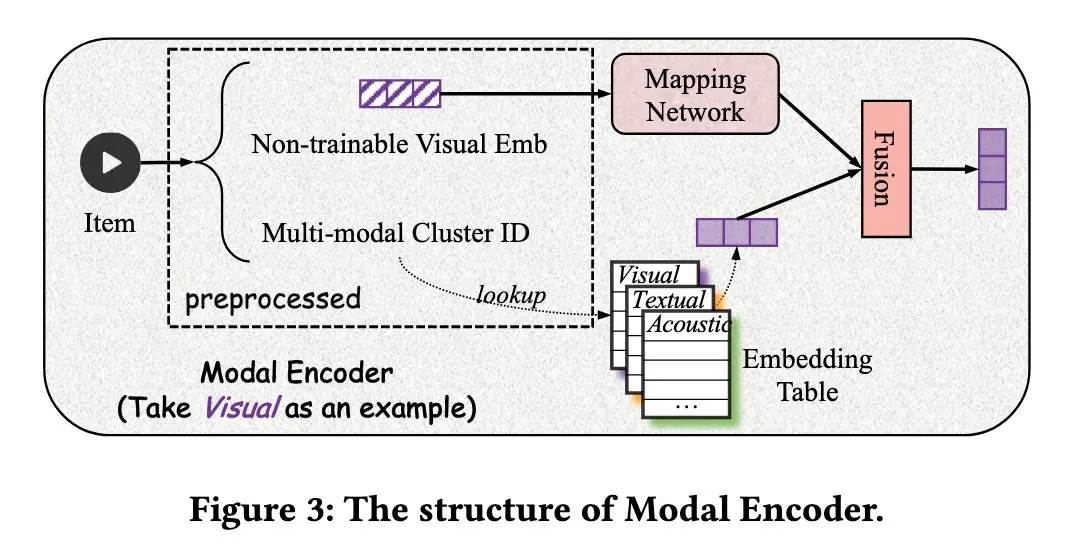

Next, cluster IDs are embedded through a Modal Encoder, a dense network translating content features into behaviorally aligned spaces and assigning trainable embeddings. The Modal Encoder uses a dense network to learn the mapping from content-space to behavior space and a cluster ID lookup to assign a trainable cluster ID embedding.

On the user side, M3CSR learns on user behavior sequences to train sequential models that capture user preferences. In addition, to accurately model user modality preferences, the framework concatenates general behavioral interests with modality-specific interests. These modality-specific interests are derived by converting item IDs back into their multimodal embeddings using the same Modal Encoder.

Results: M3CSR outperformed several multimodal baselines such as VBPR, MMGCN, and LATTICE. Ablation studies highlighted the importance of modeling modality-specific user interests and demonstrated consistent superiority of multimodal features over single-modal features across datasets (Amazon, TikTok, Allrecipes). A/B testing measured that clicks increased by 3.4%, likes by 3.0%, and follows by 3.1%. In cold-start scenarios, M3CSR also showed improved performance, achieving a 1.2% boost in cold-start velocity and a 3.6% increase in cold-start video coverage.

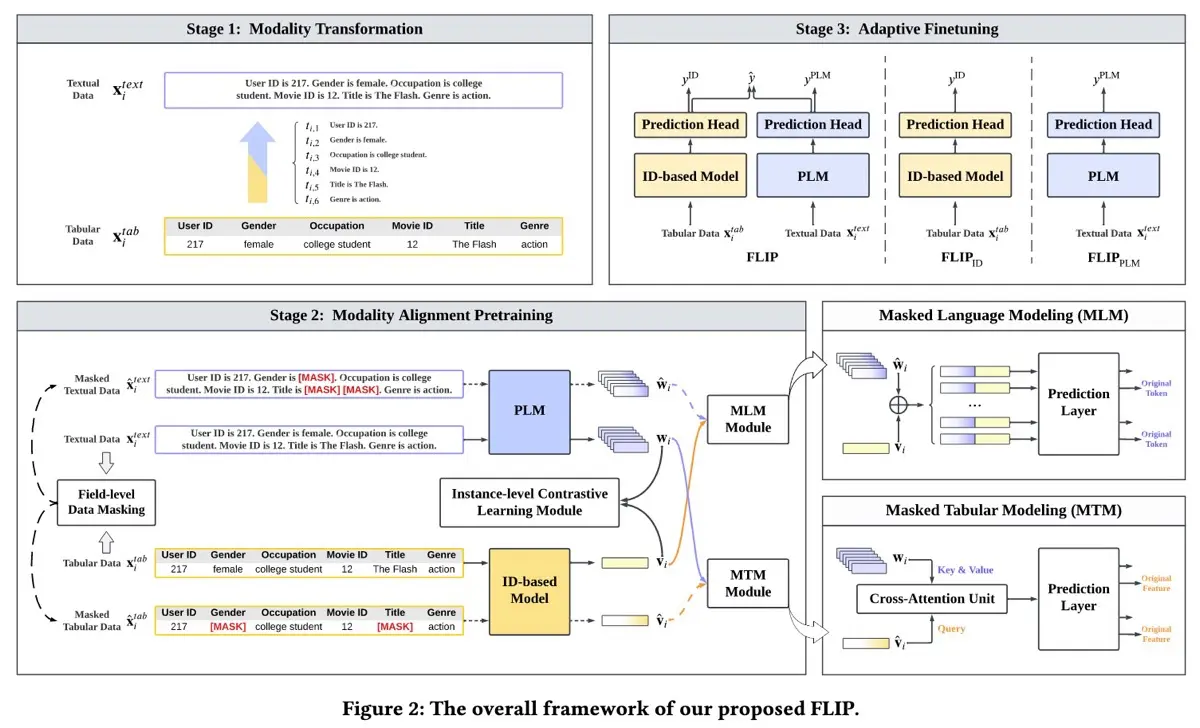

FLIP (Huawei) shows how to align ID-based recommendation models with LLMs by jointly learning from masked tabular and language data. The core idea is to reconstruct masked features from one modality (user and item IDs) using information from another modality (text tokens), ensuring tight cross-modal alignment.

FLIP operates in three stages: modality transformation, modality alignment pretraining, and adaptive finetuning. First, tabular data is translated into text using structured prompt templates. Then, joint masked language/tabular modeling is conducted to achieve fine-grained alignment between modalities. During pretraining, textual data undergoes field-level masking (replacing entire fields with [MASK] tokens), while corresponding tabular features are masked by substituting feature IDs with [MASK].

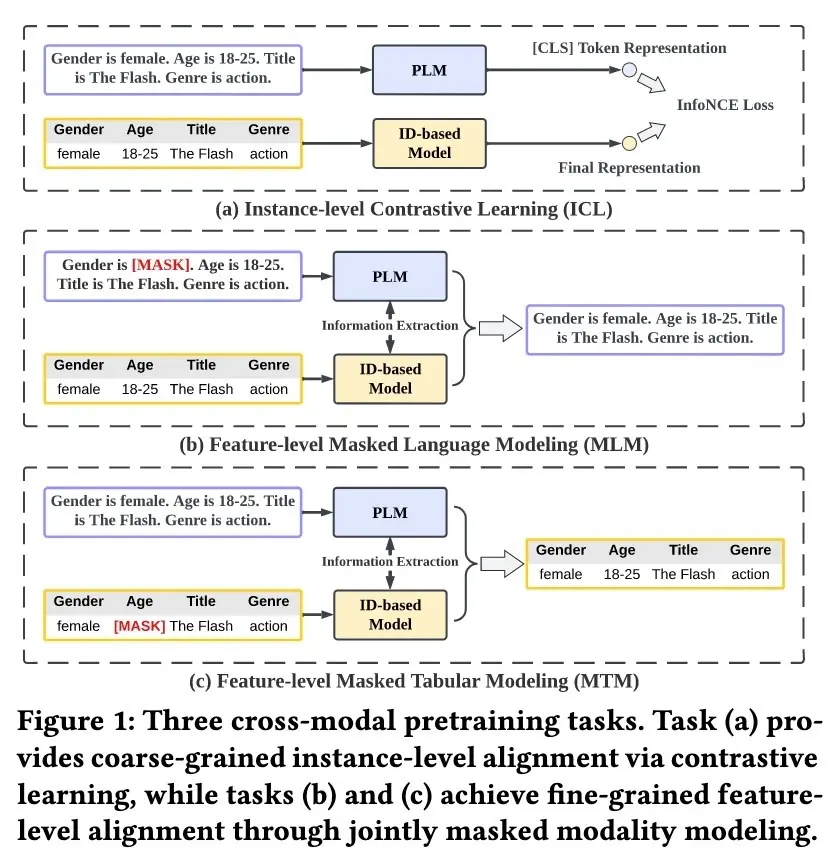

FLIP trains two parallel models with three objectives: (i) Masked Language Modeling (MLM) predicts masked text tokens using complete tabular context; (ii) Masked Tabular Modeling (MTM) predicts masked feature IDs leveraging textual data; and (iii) Instance-level Contrastive Learning (ICL) aligns global representations across modalities.

Finally, the aligned models—TinyBERT as the LLM and DCNv2 as the ID-based model—are finetuned on the downstream click-through rate (CTR) prediction task. To do this, FLIP adds randomly initialized output layers on both models to estimate click probabilities. The final prediction is a weighted sum of both models’ outputs, where the weights are learned adaptively during training.

Results: FLIP outperforms the baselines of ID-only, LLM-only, and ID+LLM models. Ablation studies show that (i) both MLM and MTM objectives improve performance, (ii) field-level masking is more effective than random token masking, and (iii) joint reconstruction between modalities is key.

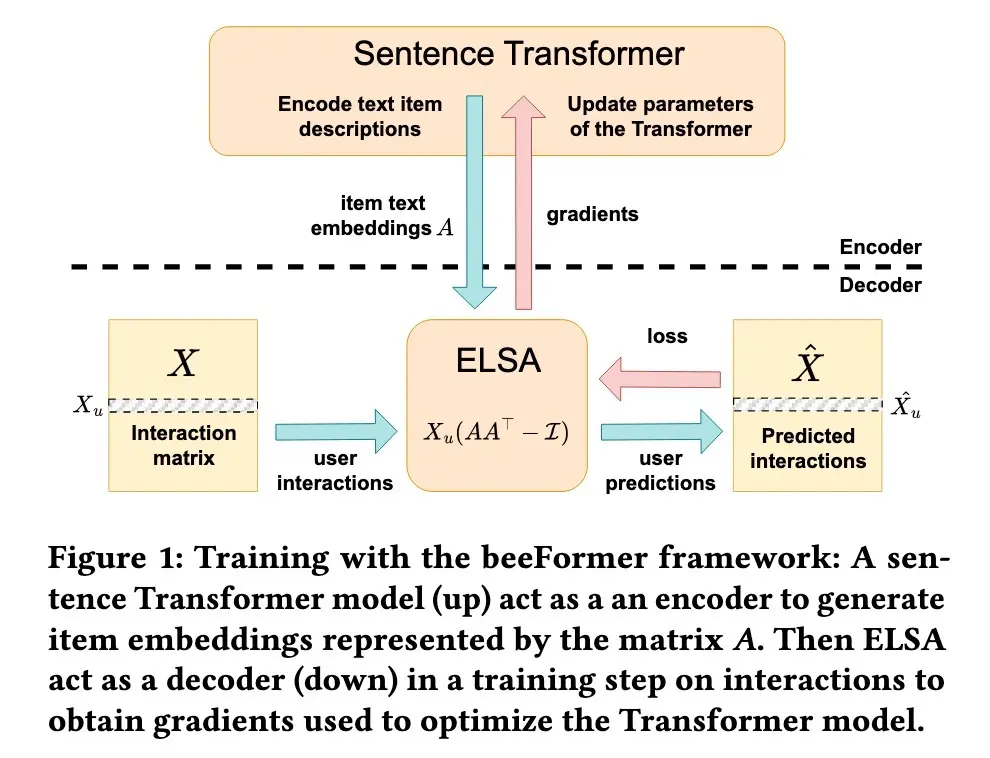

Similarly, beeFormer demonstrates how to train language-only Transformers on user-item interaction data enriched with textual information. The goal is to bridge the gap between semantic similarity (from textual data) and interaction-based similarity (from user behavior).

beeFormer combines a sentence Transformer encoder for item embeddings with an ELSA (scalablE Linear Shallow Autoencoder)-based decoder that captures patterns from user-item interactions. First, item embeddings are generated through a Transformer trained on textual data. These embeddings are then used to compute user recommendations via ELSA’s low-rank approximation of item-to-item weight. The key here is to backpropagate the gradients from the recommendation loss through the Transformer model. As a result, weight updates capture interaction patterns rather than just semantic similarity.

To make training computationally feasible on large catalogs, beeFormer applies gradient checkpointing to manage memory usage, gradient accumulation for larger effective batch sizes, and negative sampling to focus training efficiently on relevant items.

Results: Offline evaluations show that beeFormer surpasses baseline models like mpnet-base-v2 and bge-m3. However, the comparison is limited (and IMHO unfair) since the baselines weren’t finetuned on the training dataset. Interestingly, models trained across multiple domains (movies + books) performed better than domain-specific ones, suggesting that there was transfer learning across domains.

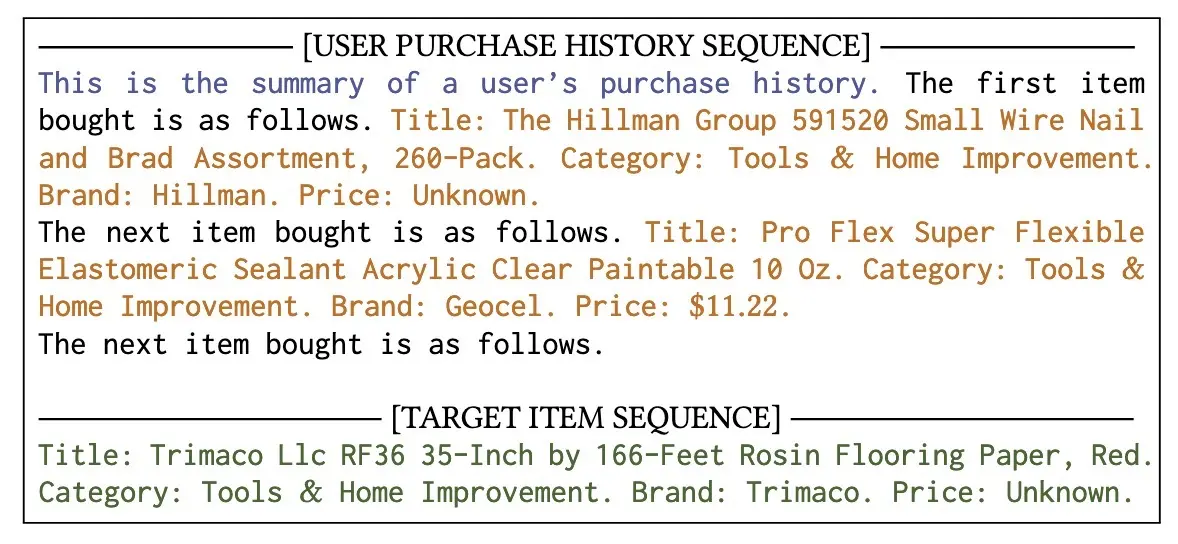

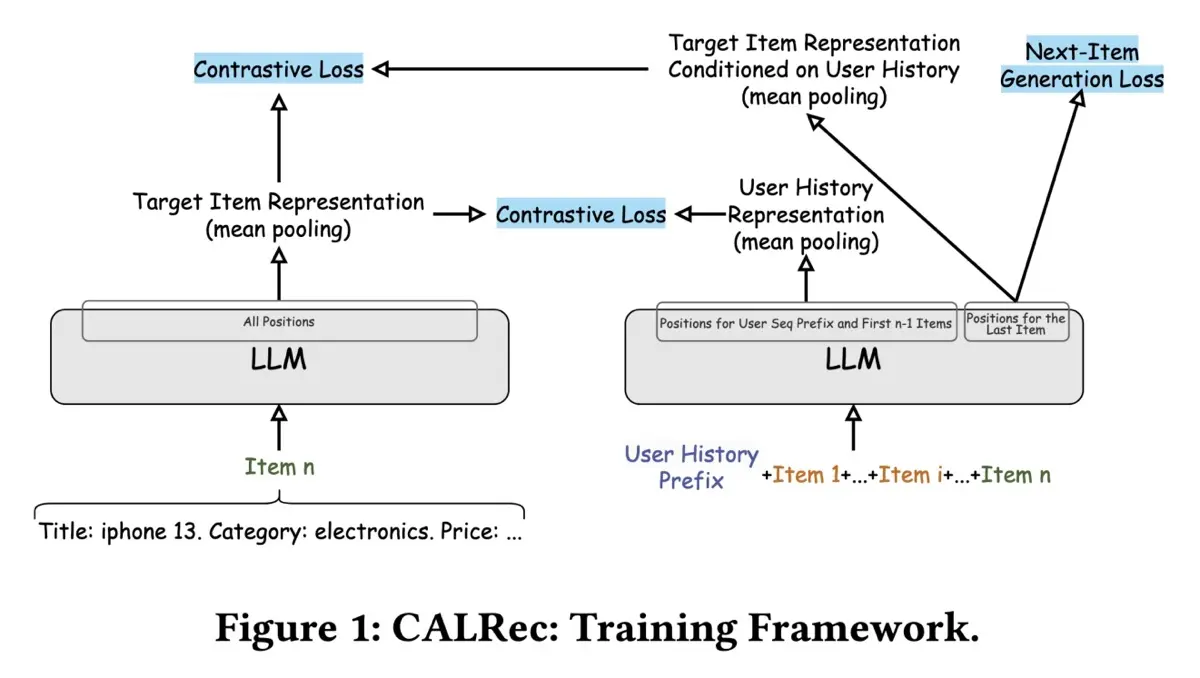

CALRec (Google) introduces a two-stage framework that finetunes a pretrained LLM (PaLM-2 XXS) for sequential recommendations. Both user interactions and model predictions are represented entirely through text.

First, all input (e.g., user-item interactions) is converted into text sequences by concatenating meaningful attributes (title, category, brand, price) into structured textual prompts. Attributes are formatted in the style of “Attribute name: Attribute description” and concatenated. At the end of the user history sequence, they append the item prefix, thus prompting the LLM to predict the user’s next purchase as a sentence completion task.

CALRec has a two-stage finetuning approach. The first stage involves multi-category training to adapt the model to sequential recommendation patterns in a category-agnostic way. The second stage refines the model within specific item categories. The training objective combines next-item generation tasks (predicting textual descriptions of items) with auxiliary contrastive alignment. The former aims to generate the text description of the target item given the user’s history; the latter applies contrastive loss on the output of the separate user and item towers to align user history to target item representations.

During inference, the model is prompted to generate multiple candidates via temperature sampling. They remove duplicates, sort by the output’s log probabilities in descending order, and keep the top k candidates. Then, these textual predictions are matched to catalog items via BM25 and sorted by the matching scores.

Results: On the Amazon Review Dataset 2018, CALRec outperforms ID-based and text-based baselines (e.g., SASRec, BERT4Rec, FDSA, UniSRec). While the evaluation dataset is limited, CalRec beating the baselines is promising. Ablations demonstrate the necessity of both training stages, especially highlighting transfer learning benefits from multi-category training and incremental gains (0.8 - 1.7%) from contrastive alignment.

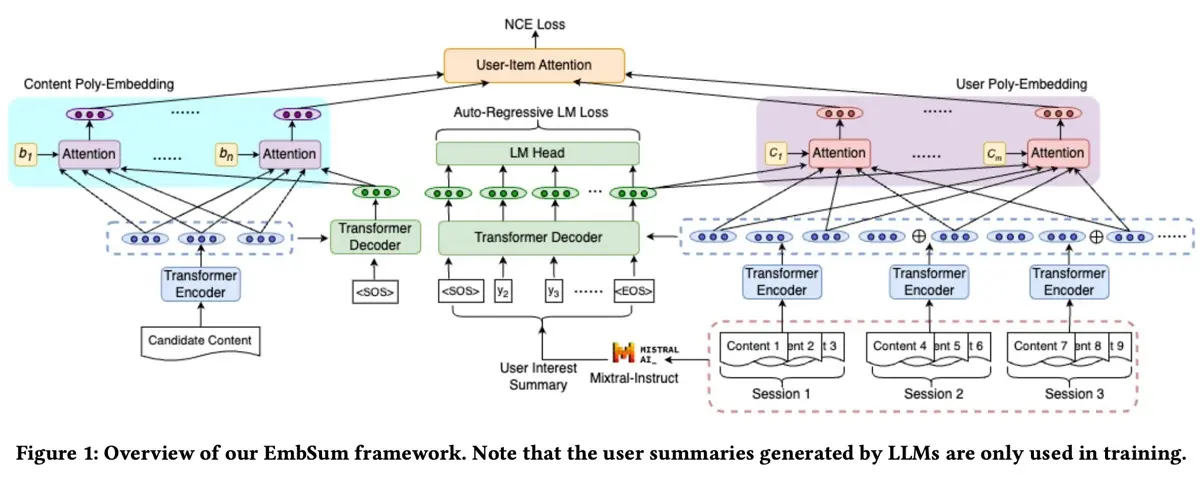

EmbSum (Meta) presents a content-based recommendation approach using precomputed textual summaries of user interests and candidate items to capture interactions within the user engagement history.

EmbSum uses T5-small (61M parameters) to encode user interactions and candidate content, managing long user histories by partitioning them into sessions for encoding. Then, Mixtral-8x22B-Instruct generates the interpretable user interest summaries from user histories. These summaries are then fed into the T5’s encoder to derive final embeddings.

Key to this architecture are User Poly-Embeddings (UPE) and Content Poly-Embeddings (CPE). To get a global representation for UPE, they take the last token of the decoder output ([EOS]) and concatenate it with the representation vectors from the session encoder. This combined representation passes through a poly-attention layer which distills nuanced user interests into multiple embeddings. EmbSum training combines noisy contrastive estimation loss and summarization loss, ensuring high-quality user embeddings.

Results: EmbSum beats several state-of-the-art content-based recommenders. Nonetheless, direct comparisons with behavioral recommenders were glaringly absent. Ablation studies show that CPE contributes most to performance, followed by session-based grouping and encoding, user poly-embeddings, and summarization losses. Additionally, GPT-4 evaluations indicate strong interpretability and quality of generated user interest summaries.

• • •

LLM-assisted data generation and analysis

Another common theme is using LLMs to enrich data. Several papers share about using LLMs to tackle data scarcity and enhance the quality of search and recommendations. Examples include generating webpage metadata at Bing, creating synthetic training data to identify poor job matches at Indeed, adding semantic labels for query understanding at Yelp, crafting exploratory search queries at Spotify, and enriching music playlist metadata at Amazon.

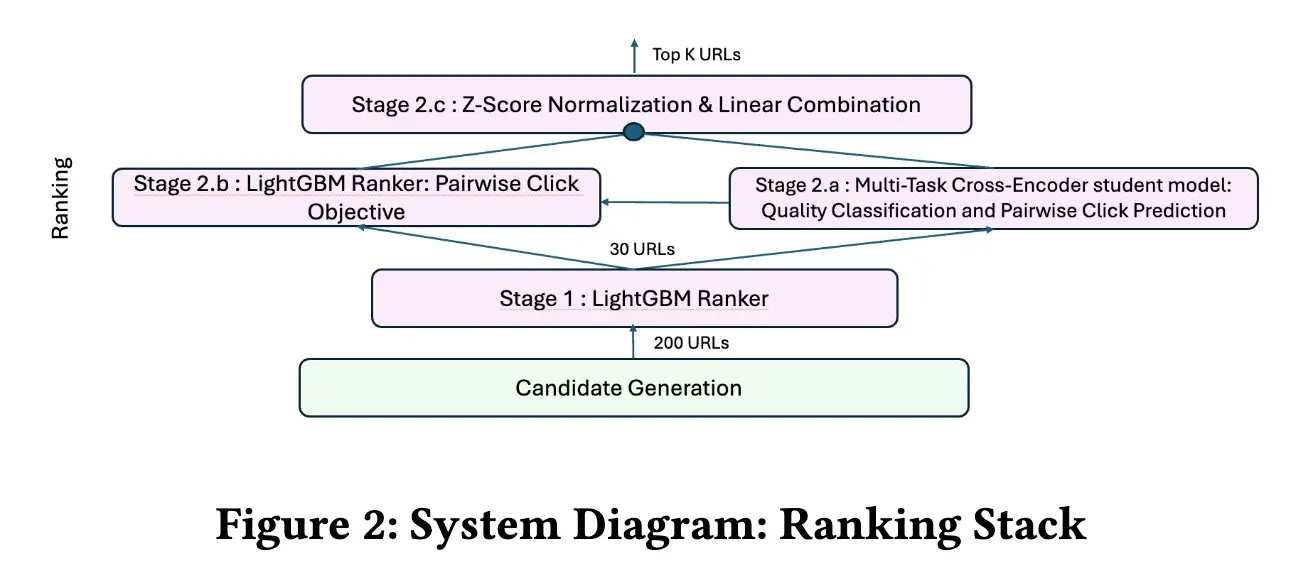

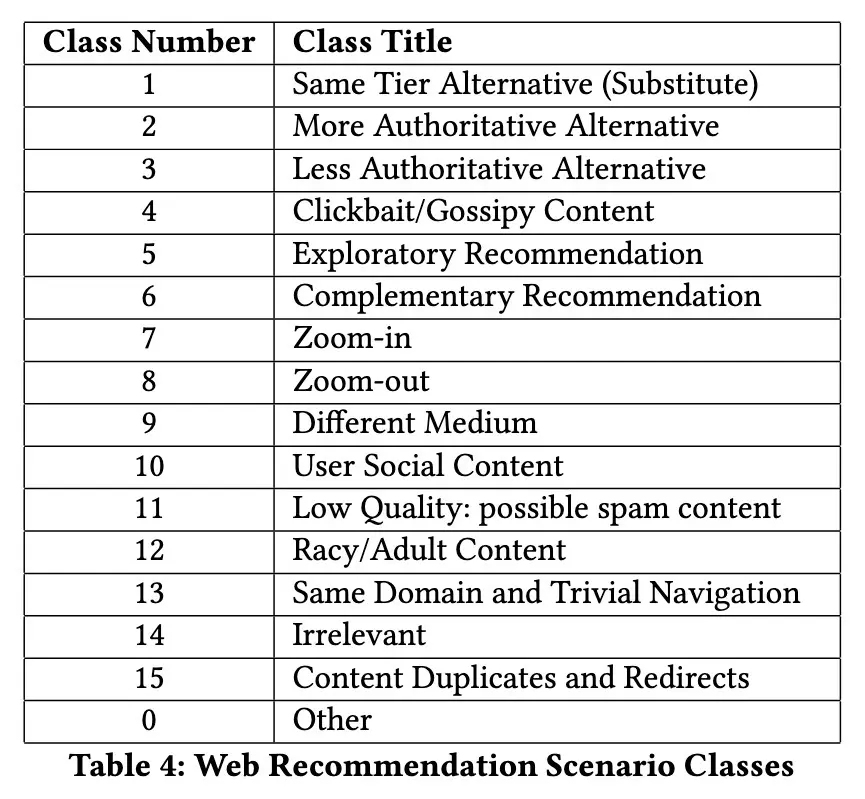

Recommendation Quality Improvement (Bing) shares how Bing improved webpage recommendations by using LLMs to generate high-quality metadata and training an LLM to predict clicks and quality.

Previously, Bing’s webpage representations relied on extractive summaries, which often caused query classification failures. To address this, they used GPT-4 to generate high-quality titles and snippets from full webpage content for two million pages. Then, for efficient large-scale deployment, they finetuned a Mistral-7B model using this GPT-4-generated data.

To improve webpage-to-webpage recommendation rankings, they finetuned a multitask MiniLM-based cross-encoder on both pairwise click predictions and quality classification tasks. The resulting quality scores were then linearly combined with click predictions from an existing LightGBM ranker.

The MiniLM (right) is ensembled with the LightGBM ranker (left).

To better understand user preferences, they defined 16 distinct recommendation scenarios reflecting common user patterns. Using high-precision prompts, they classified each webpage-to-webpage recommendation, incorporating the enhanced title and snippets from Mistral-7B, into these scenarios. Then, by monitoring the distribution changes of each scenario, they quantified the improvements in webpage recommendation quality.

Results: The enhanced system reduced clickbait by 31%, low-authority content by 35%, and duplicate content by 76%. At the same time, higher authority content increased by 18%, cross-medium recommendations rose by 48%, and recommendations with greater specificity improved by 20%. This is despite lower-quality content (e.g., clickbait) historically showing higher CTR, demonstrating the effectiveness of the quality-focused cross-encoder.

(👉 Recommended read) Expected Bad Match (Indeed) shares how they used LLM-generated labels to filter poor job matches. Specifically, they finetuned LLMs to evaluate recommendation quality and generate labels for a post-processing classifier.

They started with building an evaluation set by cross-reviewing 250 matches, narrowing it down to 147 high confidence labeled examples. Then, they prompted various LLMs, such as Llama2 and Mistral-7B, using expert recruitment guidelines to evaluate match quality across dimensions like job descriptions, resumes, and user interactions. However, these models struggled with detailed prompts, producing generalized assessments that didn’t consider detailed job and job seeker information. On the other hand, GPT-4 performed better but was prohibitively expensive.

To balance cost and effectiveness, the team finetuned GPT-3.5 on a curated dataset of over 200 human-reviewed GPT-4 responses. This finetuned GPT-3.5 matched GPT-4’s performance at just a quarter of the cost and latency. But despite the improvements, its inference latency of 6.7 seconds remained too high for online use. Thus, they trained a lightweight classifier, eBadMatch, using LLM-generated labels and categorical features from job descriptions, resumes, and user activity. In production, a daily pipeline samples job matches, engineers features, anonymizes data, generates LLM labels, and retrains the model. This classifier acts as a post-processing filter to remove low-quality matches.

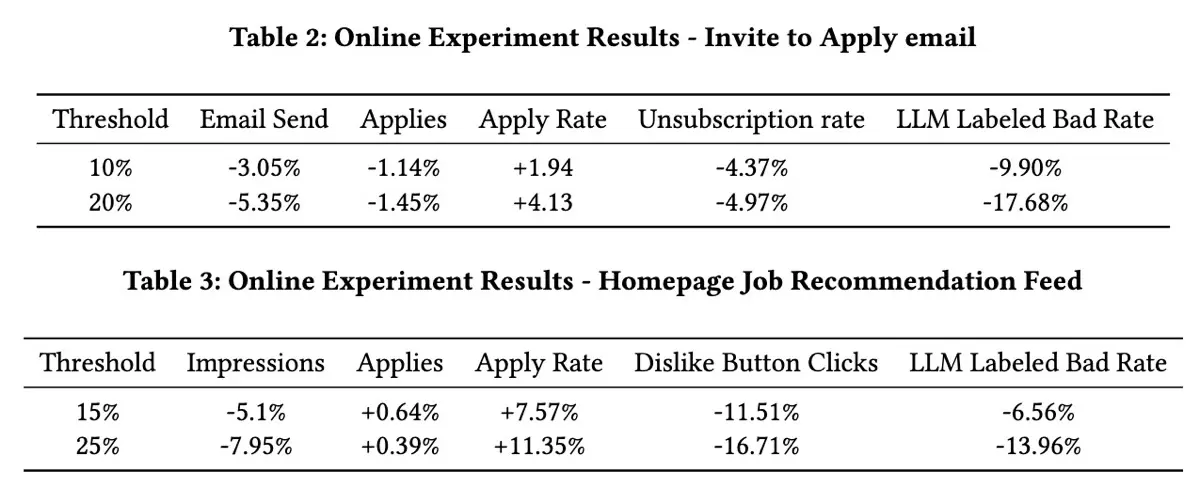

Results: The eBadMatch classifier achieved an AUC-ROC of 0.86 against LLM labels, with latency suitable for real-time filtering. Online experiments demonstrated that applying a 20% threshold filter on invitation-to-apply emails reduced batch matches by 17.68%, lowered unsubscribe rates by 4.97%, and increased application rates by 4.13%. Similar improvements were observed in homepage recommendation feeds.

(👉 Recommended read) Query Understanding (Yelp) shows how they integrated LLMs into their query understanding pipeline to improve query segmentation and review highlights.

Query segmentation identifies meaningful parts of user queries—such as topic, name, time, location, and question—and tags them accordingly. Along the way, they learned that spelling correction and segmentation could be done together and thus added a meta tag to mark spell-corrected sections and combined both tasks into a single prompt. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) further improved segmentation accuracy by incorporating business names and categories as context that disambiguated user intent. For evaluation, they compared LLM-identified segments against human-labeled datasets of name match and location intent.

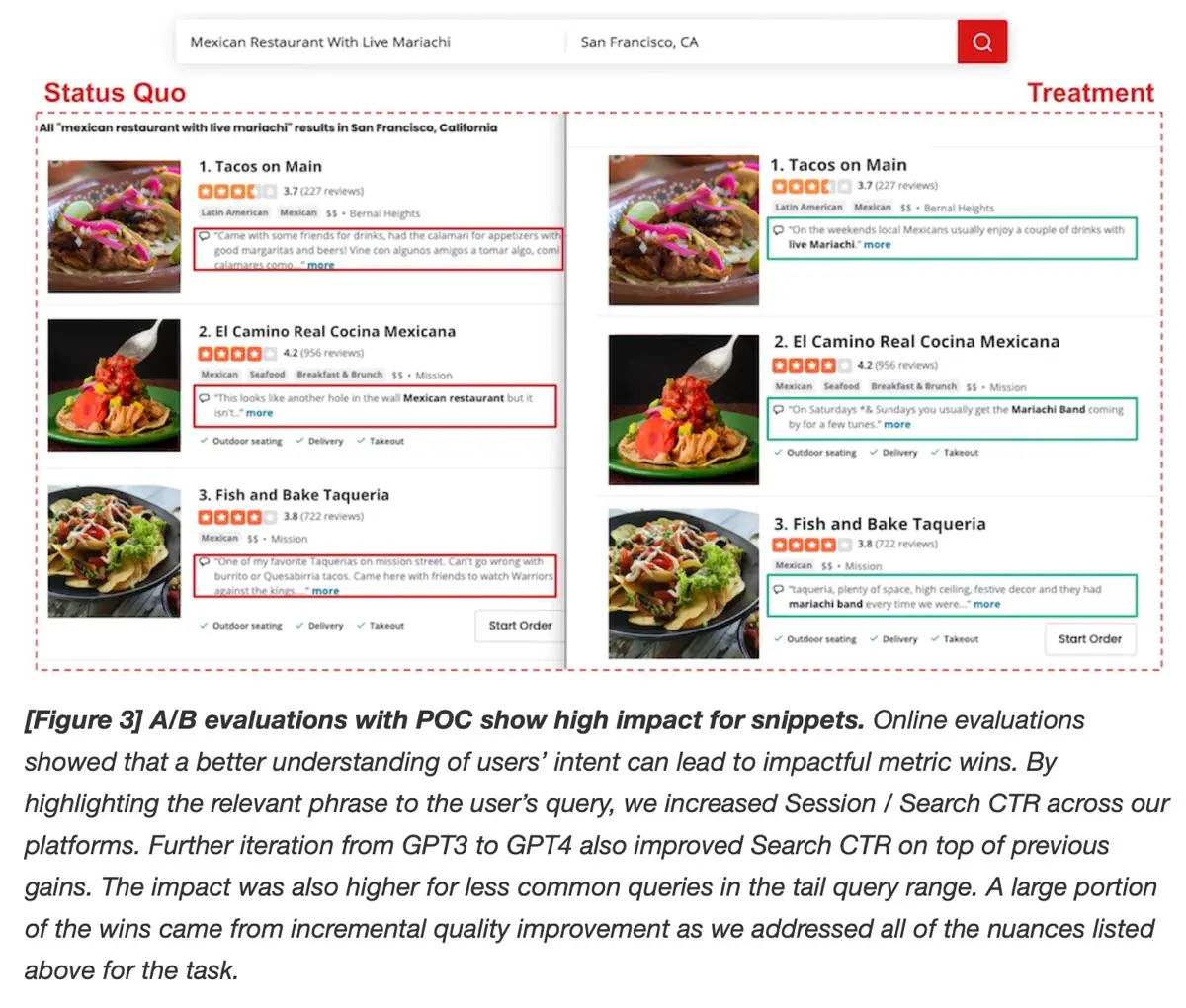

Review highlights selects key snippets from reviews to highlight in search results. They used LLMs to generate synonymous phrases suitable for highlights. Curated examples prompted LLMs to replicate human reasoning in phrase expansion. RAG further enhanced relevance by augmenting the input with relevant business categories to guide phrase generation. Offline evaluation was done via human annotators before online A/B testing of the new highlight phrases. To scale efficiently and cover 95% of traffic, Yelp pre-computed snippet expansions using batch calls to OpenAI and stored them in key-value stores to reduce latency.

The team shared their approach—from initial formulation and proof of concept (POC) to scaling up. Initially, they assessed LLM suitability and defined the project’s scope. During POC, they leveraged the power-law distribution of queries, caching pre-computed LLM responses for common queries covering most traffic. To scale, they created golden datasets using GPT-4 outputs and finetuned smaller, cost-effective models like GPT-4o-mini. Additionally, real-time models like BERT and T5 addressed less frequent, long-tail queries.

Results: Yelp’s query segmentation significantly improved location intent detection, while enhanced review highlights increased both session and search click-through rates (CTR), especially benefiting long-tail queries.

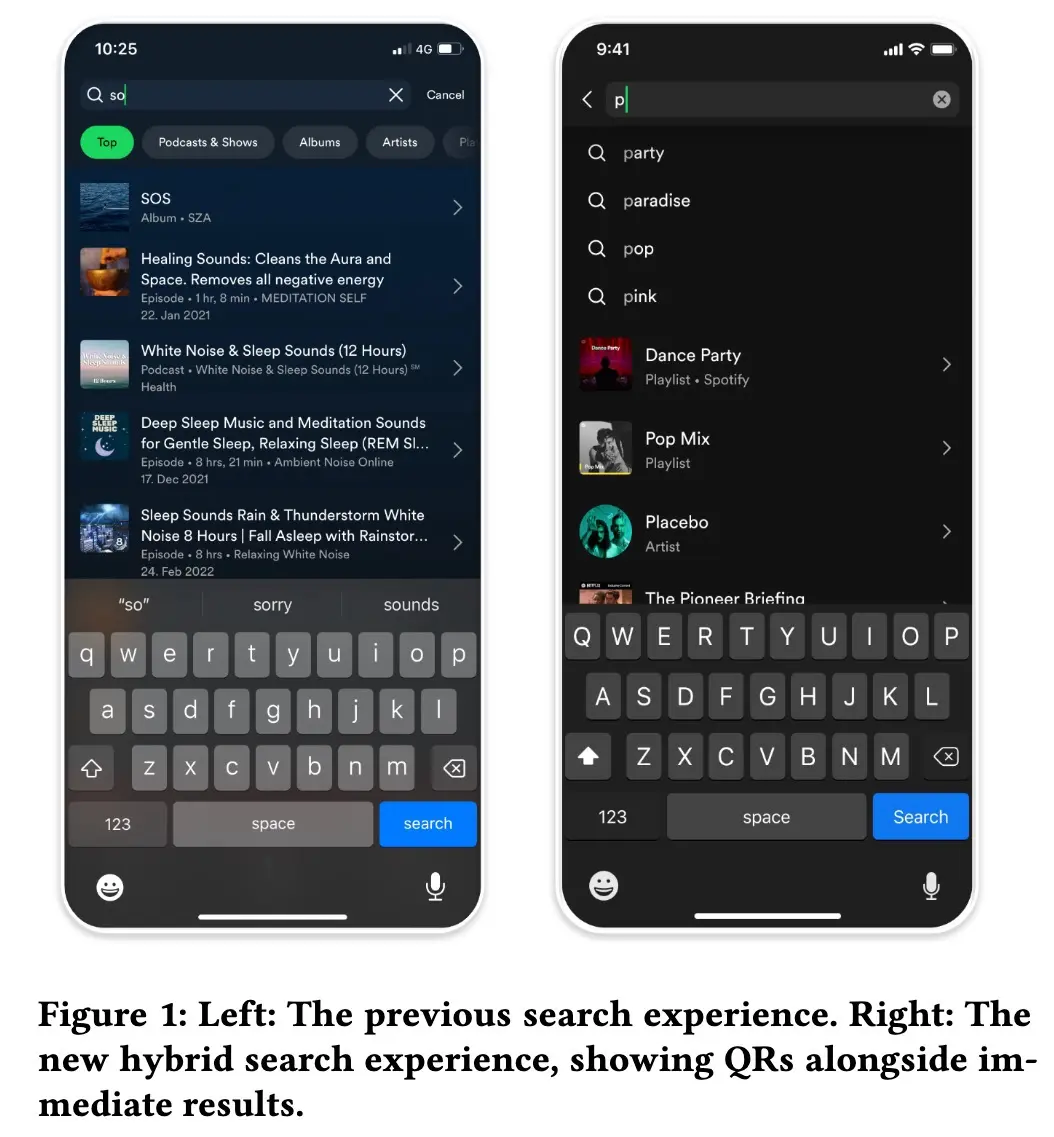

Query Recommendations (Spotify) details how they built a hybrid query recommendation system to suggest exploratory search queries alongside direct results. This approach was necessary to support Spotify’s expansion beyond music to podcasts, audiobooks, and diverse content types by helping users explore those content.

Spotify generated query suggestions by (i) extracting from catalog titles, playlist names, and podcasts, (ii) mining suggestions from search logs, (iii) leveraging users’ recent searches, (iv) applying metadata and expansion rules (e.g., “artist name” + “covers”), and (v) generating synthetic natural language queries via LLMs. To generate synthetic queries, techniques such as Doc2query and InPars were used to broaden query variations, enhancing exploratory searches and mitigating retrievability bias.

The query suggestions were then combined with regular results and ranked by a point-wise ranker optimized for downstream user actions like streaming or adding content to playlists. The ranker use features such as lexical matching, query statistics, retrieval scores, and user consumption patterns. For personalization, they relied on vector representations of users and query suggestion candidates.

Results: Spotify saw a 9% increase in exploratory intent queries, a 30% rise in maximum query length per user, and a 10% increase in average query length—this suggests the query recommendation updates helped users express more complex intents. An online ablation showed the ranker’s removal caused a 20% decline in clicks on recommendations, underscoring its importance.

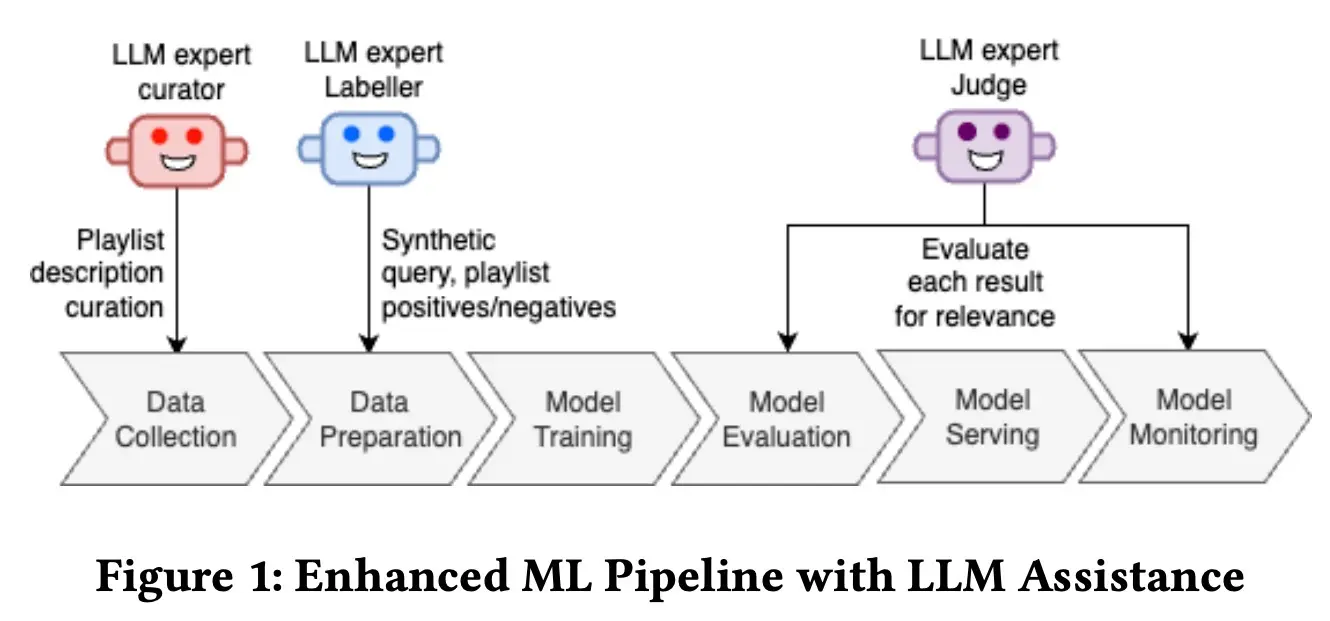

Playlist Search (Amazon) discusses Amazon’s integration of LLMs into playlist search pipelines to tackle challenges like data scarcity, metadata enrichment, and scalable evaluation while reducing reliance on manual annotation.

To enrich metadata, they used LLMs (LLM curator) to create detailed descriptions for community playlists based on their initial 15 tracks, capturing themes, genres, activities, and artists. (These community playlists typically only had a playlist title.) This addressed data scarcity in community-generated content. Then, Flan-T5-XL was finetuned to scale this inference process.

They also applied LLMs to generate synthetic queries paired with playlists (and associated metadata) to create training data for bi-encoder models. These pairs were generated and scored by an LLM (LLM labeler) to maintain balanced positive and negative examples. Lastly, they used an LLM (LLM judge), guided by human annotations and careful prompting to ensure alignment, to streamline evaluations.

Results: Integrating LLMs led to substantial double-digit recall improvements across benchmarks, SEO, and paraphrasing datasets. Overall, the use of LLMs helped overcome the challenges of data scarcity and evaluation scalability without extensive manual effort.

• • •

Scaling Laws, transfer learning, distillation, LoRAs

Another trend is the adoption of training approaches from large language models (LLMs) and computer vision into recommender systems. This includes exploring scaling laws (how model size and data quantity affect performance), using knowledge distillation to transfer insights from large models to smaller, efficient ones, applying cross-domain transfer learning to handle limited data, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques such as LoRAs.

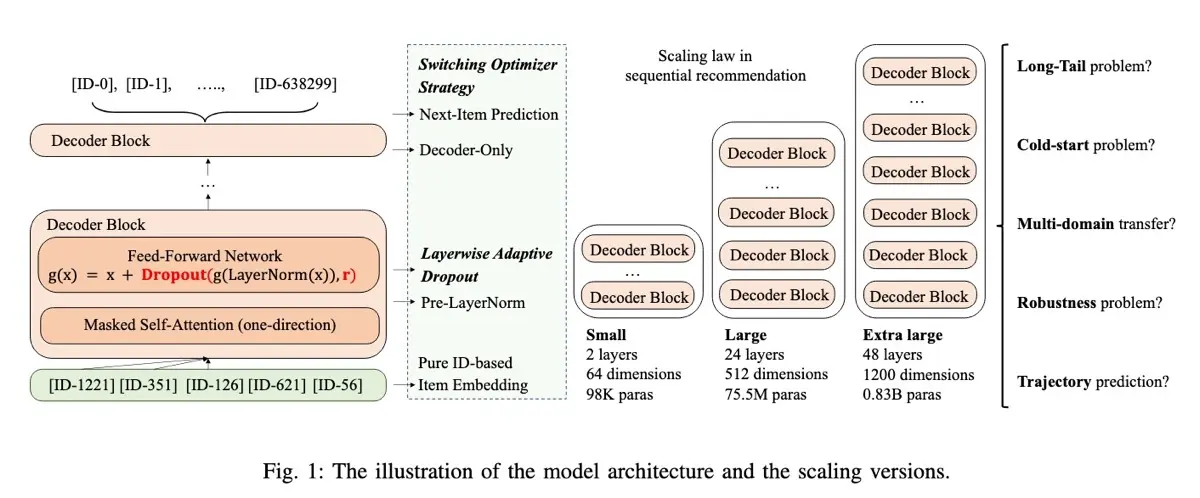

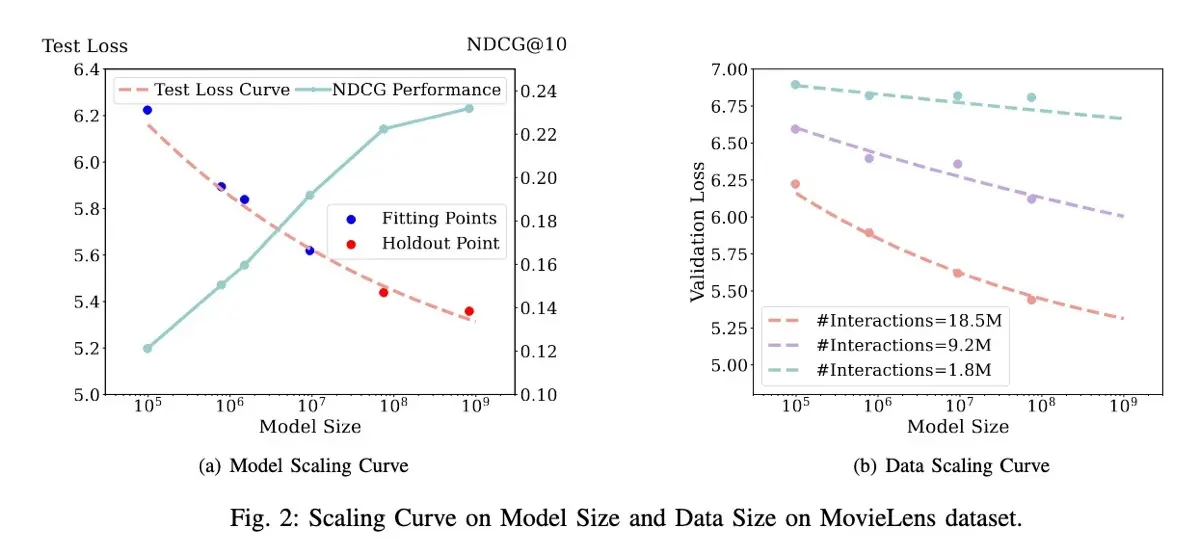

(👉 Recommended read) Scaling Laws investigates how the performance of ID-based sequential recommender models improve as their model size and data scale increase. The authors uncovered a predictable power-law relationship where performance consistently improves as the size of both models and datasets expands.

They adopt a decoder-only transformer architecture, experimenting with models ranging from 98.3K to 0.8B parameters. They evaluated these models on the MovieLens-20M and Amazon-2018 datasets. For the Amazon dataset, interaction records from 29 domains were combined, sorted chronologically, and simplified to include only item IDs without additional metadata. The datasets were then formatted into fixed-length sequences of 50 items each; shorter sequences were padded and longer ones were truncated. The model is then optimized to predict the next item at time step $t + 1$ conditioned on the previous $t$ items.

To tackle instability in training larger models, the authors introduced two key improvements. First, they implemented layer-wise adaptive dropout, applying higher dropout rates in lower layers and lower dropout rates in upper layers. The intuition is that lower layers process direct input from data and are more prone to overfitting. Conversely, higher layers build more abstract representations and thus benefit from less dropout to reduce information loss that could lead to underfitting.

The second improvement was dynamically switching optimizers during training—starting with Adam before switching to stochastic gradient descent (SGD) at a predefined point. This approach is motivated by the observation that Adam quickly reduces loss in early training phases but ultimately SGD achieves better convergence.

Results: Unsurprisingly, increased model capacity (excluding embedding parameters) consistently reduced cross-entropy loss. They modeled this with a power-law curve and accurately predicted performance for larger models (75.5M and 0.8B params). Similarly, they observed that larger models could achieve lower losses even with smaller datasets, whereas smaller models needed more data to reach comparable performance. For example, a smaller 98.3K-parameter model required twice the data (18.5M interactions) compared to a larger 75.5M-parameter model (9.2M interactions) to attain similar performance.

Regarding data repetition, models of sizes 75.5M and 98.3K parameters continued improving beyond a single training epoch, with notable gains observed from two to five epochs. Surprisingly, changing model shape had minimal impact on performance. Ablation studies showed that layer-wise adaptive dropout and optimizer switching substantially enhanced performance in larger models (24 layers), though smaller models (2 layers) remained largely unaffected. Further ablations on five challenging recommendation tasks highlighted the advantage of larger models, particularly for long-tail items and cold-start users.

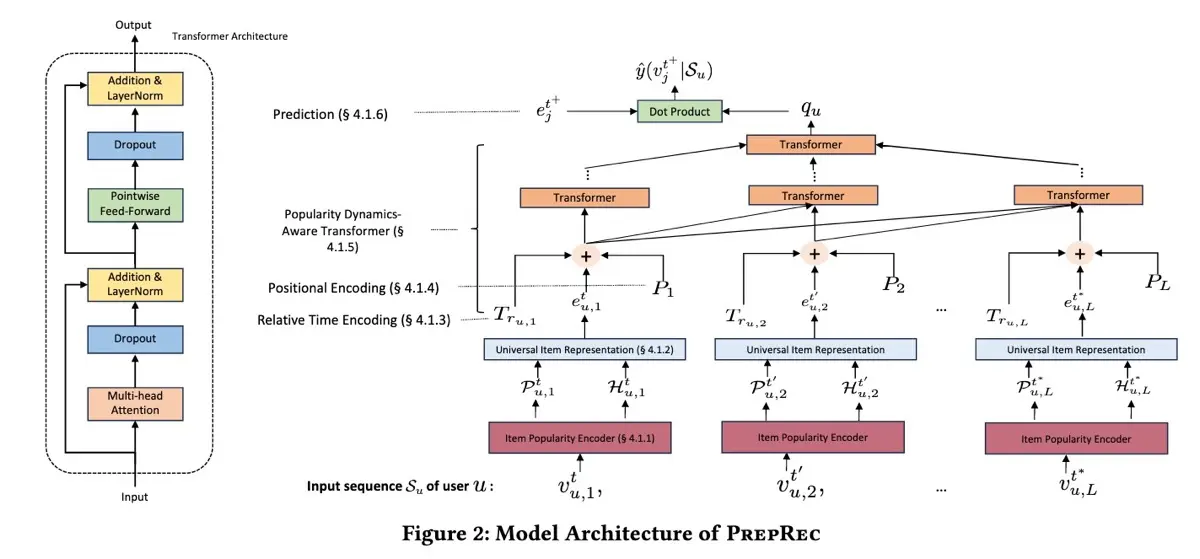

PrepRec shows how pretraining can be adapted to recommender systems, enabling cross-domain, zero-shot recommendations. The key innovation is leveraging item popularity dynamics derived solely from user interactions, without relying on item metadata.

PrepRec uses popularity statistics calculated over coarse (monthly) and fine (weekly) timescales. These popularity metrics are converted into percentiles and then encoded into vector representations. In addition, the model incorporates relative time intervals between user interactions and uses a fixed positional encoding for each interaction in a user’s sequence. (IMHO, while the approach is effective, it relies on several specialized techniques—coarse vs. fine-grained periods, relative time intervals, and positional encodings—which might limit its generalizability.)

For training, PrepRec has binary cross-entropy as the objective and uses Adam for optimization. The model and baselines have consistent settings: embedding dimension of 50, max sequence length of 200, and batch size of 128. During inference, PrepRec calculates item popularity dynamics from the target domain before generating recommendations via inference on the pretrained model.

Results: PrepRec achieves promising zero-shot performance, with only a minor reduction (2-6% recall@10) compared to models like SasREC and BERT4Rec which were specifically trained on the target domains. When trained from scratch on the target domains, PrepRec matches or slightly surpasses these models in regular sequential recommendations despite using just 1-5% of their parameters, thanks to not having item-specific embeddings. Ablations showed that modeling relative time intervals significantly boosted performance, and capturing both coarse and fine-grained popularity trends was essential for tracking evolving user interests.

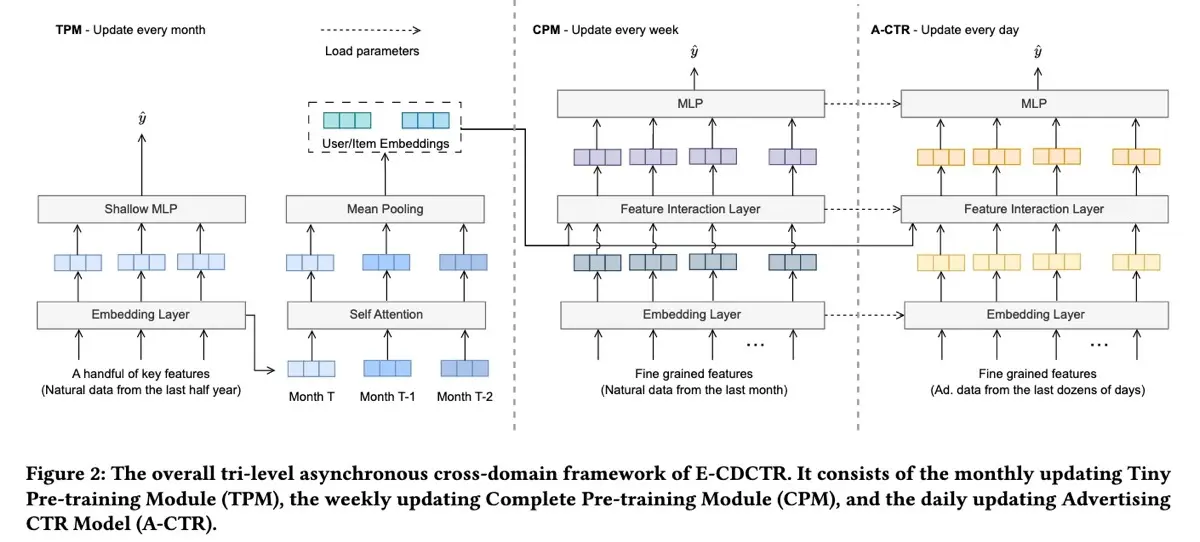

E-CDCTR (Meituan) demonstrates the potential of transfer learning by using organic item data to improve click-through rate (CTR) predictions in advertising, tackling the challenge of sparse ad data.

E-CDCTR has three components: the tiny pretraining model (TPM), complete pretraining model (CPM), and advertising CTR model (A-CTR). The TPM, a lightweight model with just embedding and MLP layers, trains monthly on six months of organic impressions and clicks. It captures long-term collaborative filtering signals via historical user and item embeddings. Features include user and item IDs, category IDs, etc.

Next, the CPM pretrains a CTR model weekly using the most recent month’s organic data and using the user and item embeddings learned by TPM. Finally, the A-CTR model is initialized from the CPM and finetuned daily on advertising-specific data. A-CTR also uses user and item embeddings from the TPM. A-CTR also uses richer features such as user behavior sequences, user context, item metadata, and feature interactions, resulting in a more sophisticated model architecture that includes sequential input, feature crosses, and a larger MLP layer.

For online inference, E-CDCTR employs user and item embeddings generated by TPM from the past three months. The A-CTR model then uses these embeddings to predict the advertising CTR. (The authors mention using self-attention to combine embeddings but provide limited details on training it.)

Results: E-CDCTR outperforms cross-domain baselines such as KEEP, CoNet, DARec, and MMoE. Ablation studies confirm the value of both TPM and CPM, with CPM having a more substantial impact. In addition, extending historical embeddings from one to three months further enhanced performance, whereas simply merging advertising data with organic data did not yield improvements.

Bridging the Gap (YouTube) shares insights on applying knowledge distillation in large-scale personalized video recommendations at YouTube.

Their recommenders are multi-objective pointwise models for ranking videos. These models simultaneously optimizing short-term objectives like video CTR and long-term objectives like the estimated long-value value of a user. Their models typically feature a teacher-student setup, with the teacher and student models sharing similar architectures though the teacher model is 2 - 4x larger than the student model.

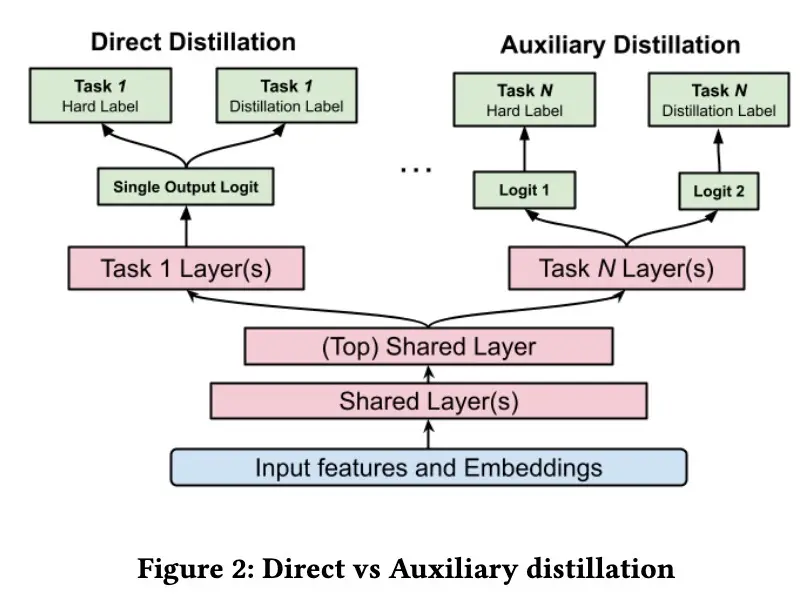

However, distribution shifts between teacher and student can cause biases. To address this, the authors propose an auxiliary distillation strategy—instead of directly using the teacher’s predictions (soft labels), they decouple the hard labels from the soft teacher predictions via separate task logits. This enables the student model to effectively learn from the teacher without inheriting unwanted biases.

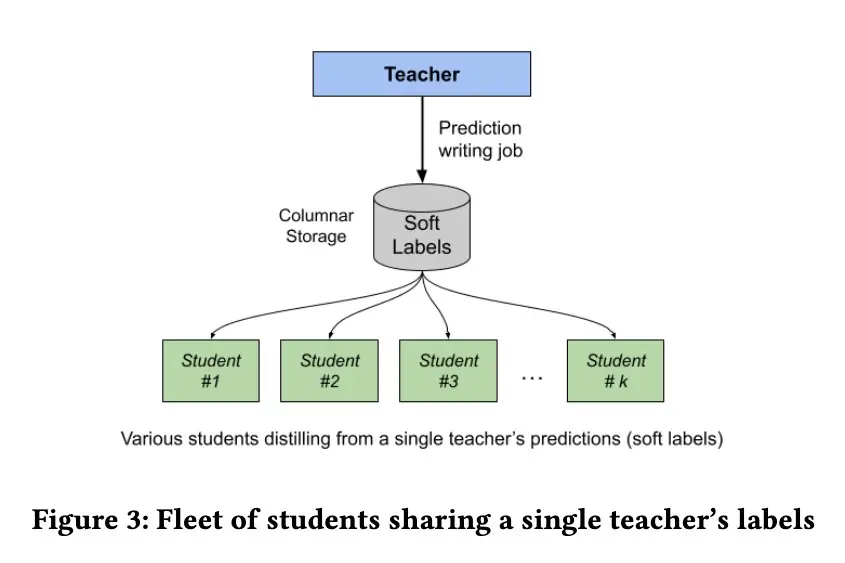

To amortize the cost of training the large teacher model, they have a single teacher improve multiple student models. As a result, a single teacher model can provide distilled knowledge to various specialized recommendation tasks, reducing redundancy and computational overhead. Teacher labels are stored in a columnar database that prioritizes read performance for the students during training.

Results: The auxiliary distillation strategy delivered a 0.4% improvement in E(LTV) prediction compared to direct distillation methods, which performed similarly to models without distillation. This confirms the auxiliary distillation approach’s effectiveness in reducing teacher noise. In ablation studies on teacher size, even a modest teacher (2x the student’s size) led to meaningful improvements (+0.42% engagement, +0.34% satisfaction) while a 4x teacher led to +0.43% engagement and +0.46% satisfaction.

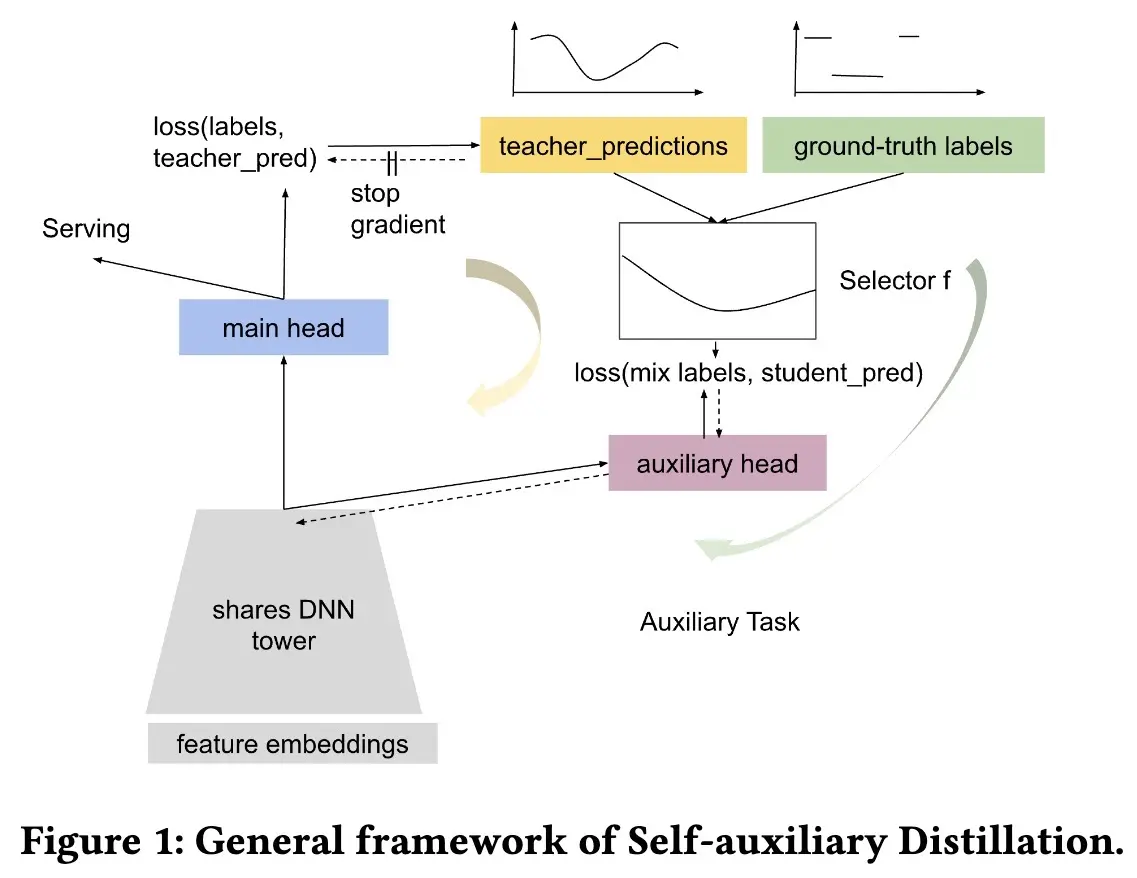

Similarly, Self-Auxiliary Distillation (Google) introduces a distillation framework aimed at improving sample efficiency for large-scale recommendation models.

The core idea is to prioritize training on high-quality labels while improving the resolution of lower-quality labels. The intuition is that positive labels provide more signal than negative labels when predicting CTR, thus it makes sense to prioritize them. On the other hand, negative labels are closer to weak positives than an absolute zero—thus, representing them with an estimated CTR value offers better training signal.

The model has a shared bottom tower with two heads: the main head (teacher) is trained directly on ground-truth labels, serving as the primary inference model and generating calibrated soft labels. Calibration is maintained by ensuring the mean prediction matches the mean of actual labels. The auxiliary head (student) learns from a mixture of these soft teacher labels and original labels, helping stabilize the training process. Specifically, the auxiliary head has a bilateral branch where one branch distills knowledge from the teacher’s soft labels and the other learns from the hard ground-truth label. A selector merges the labels from both branches using functions such as $max(y, y’)$.

Results: Self-attention distillation consistently improved recommendation quality across multiple domains including apps, commerce, and video recommendations. Ablations show that training on original ground-truth labels primarily drives performance gains, while the distillation component significantly stabilizes and aligns the model’s predictions. Training exclusively on ground-truth labels showed inconsistent results while training on the distillation labels only didn’t lead to improvements.

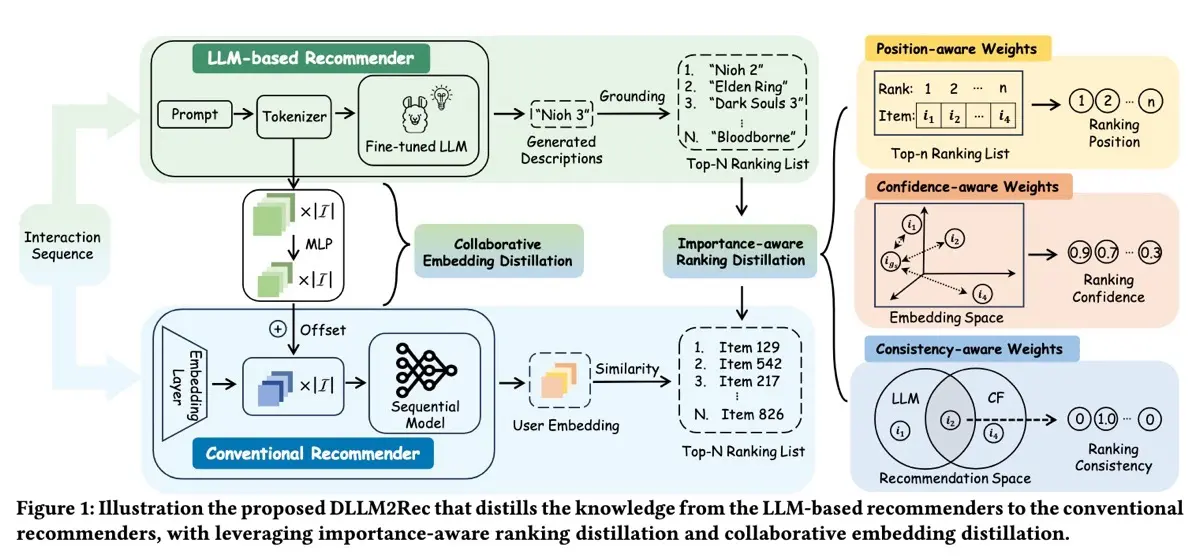

DLLM2Rec shows how to distill recommendation knowledge from LLMs into lightweight, conventional sequential recommendation models, making deployment more practical. The paper identifies three main challenges: (i) unreliable teacher knowledge/labels, (ii) the capability gap between teacher and student models, and (iii) semantic divergence between the teacher’s and student’s embedding spaces.

To tackle these issues, DLLM2Rec adopts two key strategies: importance-aware ranking distillation and collaborative embedding distillation. Importance-aware ranking distillation focuses on selecting reliable instances for training via importance weights. These weights consider factors like ranking position (prioritizing items ranked higher by the teacher), teacher confidence (evaluated through content similarity between generated descriptions and actual items), and the consistency between the teacher’s and student’s recommendations. Meanwhile, collaborative embedding distillation involves using a learnable MLP to effectively translate embeddings from the teacher’s semantic space into the student’s space.

In their experiments, they use BIGRec (built on Llama2-7B) as the teacher and three popular sequential models (GRU4Rec, SASRec, and DROS) as students.

Results: DLLM2Rec boosts the performance of student models, showing an average improvement of 47.97% across three datasets (Amazon Video Games, MovieLens-10M, and Amazon Toys and Games) when evaluating hit rate@k and NDCG@k (see Table 5 in the paper). Additionally, inference time dropped significantly, from 3-6 hours with the teacher model down to just 1.6-1.8 seconds with DLLM2Rec.

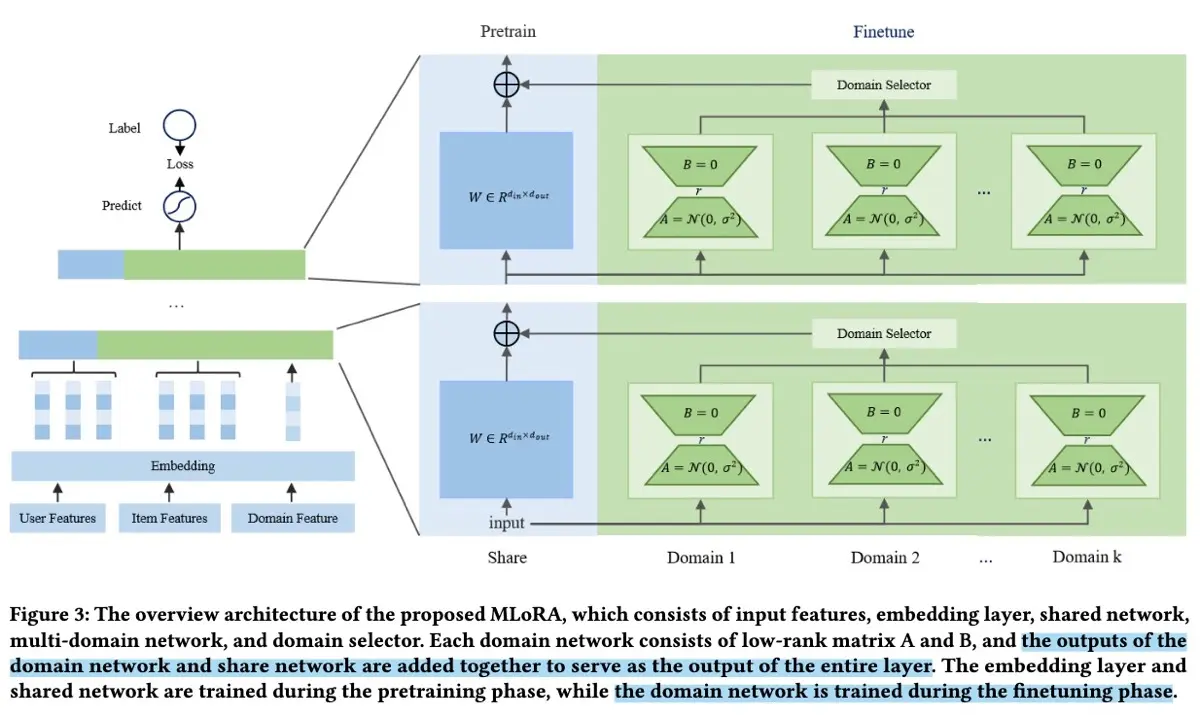

MLoRA (Alibaba) describes using domain-specific LoRAs (low-rank adapters) to enhance multi-domain CTR prediction models. It addresses two common problems: data sparsity (limited data per domain) and domain diversity (variations across domains) that typically arise when training either separate models or a single combined model respectively.

They adopt a two-step training process. First, they pretrained a shared backbone network on extensive, multi-domain data to learn generalizable patterns across domains. Then, they freeze the backbone and finetune domain-specific LoRAs on each domain’s unique data. A key challenge was adapting LoRA ranks layer-by-layer due to varying dimensions in CTR model layers. (Recommender models have different dimentions per layer unlike language models which typically have uniform dimensions.) In their experiments, all models had hidden layers of 256, 128, and 64 dimensions.

To get a sense of data distribution differences between pretraining and finetuning: During their A/B test, the pretrained backbone used 13 billion samples spanning 90 days from 10 domains, whereas finetuning involved 3.2 billion samples from just 21 days.

Results: MLoRA increased AUC by 0.5% across datasets such as Taobao-10, Amazon-6, and MovieLens. Ablation studies showed that domains with smaller datasets and higher inter-domain differences benefited more. They also found that simpler models (like MLP) performed best with lower LoRA ranks (32), while more complex models (like DeepFM) benefited from higher ranks (64 - 128). A/B testing showed substantial business gains—a 1.49% lift in CTR, a 3.37% boost in conversions, and a 2.71% increase in paid buyers—with only a modest 1.76% rise in model complexity due to the use of LoRAs.

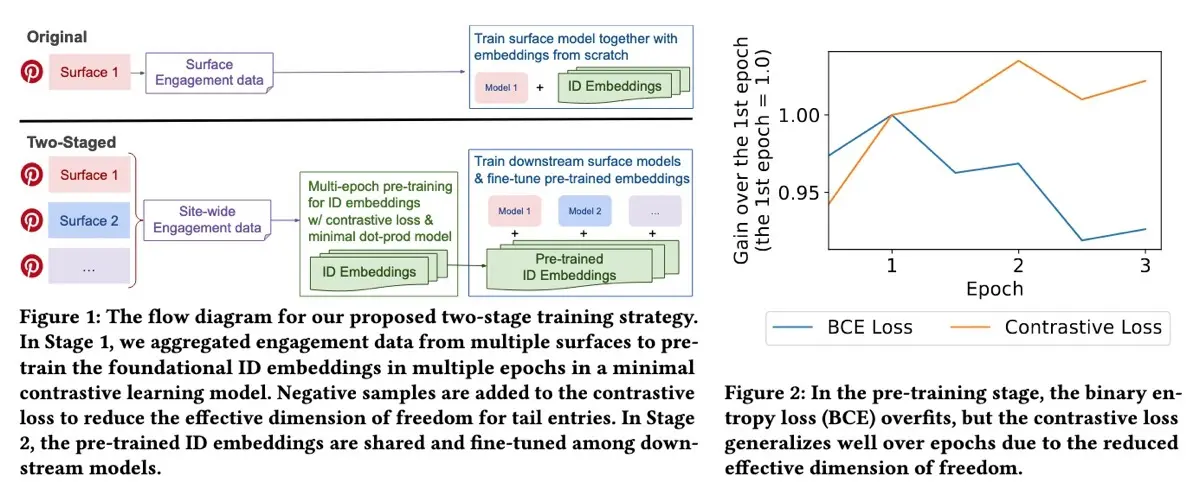

Taming One-Epoch (Pinterest) highlights the challenge of models overfitting after just one training epoch, primarily due to the long-tail nature of recommendation data. (Perhaps the Scaling Laws paper above, which showed gains beyond one epoch, used datasets (i.e., Amazon and MovieLens) that had the long-tail filtered out.) This overfitting arises because tail entries have far more degrees of freedom compared to the limited training examples available.

Here’s more context on the “one-epoch problem”: In online experiments, they saw that deep CTR models without ID embeddings typically require multiple epochs to converge. However, introducing ID embeddings often causes performance to peak after just one epoch, leading to worse results compared to multi-epoch training without ID embeddings.

Their solution involves two distinct stages. In the first stage, they pretrain foundational ID embeddings using a minimal dot-product model combined with contrastive loss, utilizing in-batch and uniformly random negatives. This contrastive approach reduces the effective dimensionality of tail entries, minimizing overfitting. Moreover, because the pretraining step is relatively lightweight, they can use a much larger dataset—around ten times the engagement data compared to the downstream recommendation model.

In the second stage, the pretrained embeddings are finetuned in task-specific models for multiple epochs. By separating embedding pretraining from downstream finetuning, they mitigate overfitting and get better results compared to merely freezing the embeddings.

Results: In Figure 2 above, the typical binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss tends to overfit after the first epoch, whereas the contrastive loss remains stable. Ablation studies revealed that a single-stage training method underperformed relative to baseline models due to severe overfitting (−3.347% for Homefeed and −1.907% for Related Pins). Conversely, the two-stage training consistently yielded superior results (+1.323% Homefeed, +2.187% Related Pins), and in online A/B tests, led to a significant overall engagement lift of 2.2%.

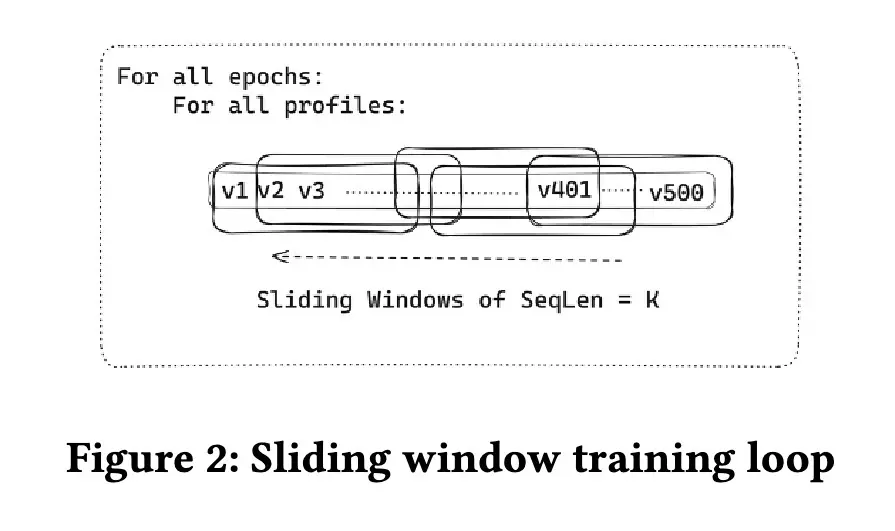

Sliding Window Training (Netflix) describes their method for efficiently training on long user history sequences without incurring the memory and latency costs associated with large input sizes. One workaround is to truncate user historical interactions—however, this comes at the cost of not using valuable information from the entire user journey.

Their solution is elegantly simple. Assuming a baseline model that only handles sequences of up to 100 items, they introduce a sliding window sampler during training. This sampler selects different segments of user history in each training epoch, allowing the model to learn on long-term user patterns. Additionally, they experimented with mixing epochs—some focused exclusively on sliding windows, while others emphasized only the latest 100 interactions—to balance between recent user behavior and historical preferences.

Results: Offline evaluations showed the sliding window method consistently outperformed models trained solely on the most recent 100 interactions. Specifically, a pure sliding window variant slightly reduced Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) by 1.2%, but improved Mean Average Precision (MAP) by 1.5% and recall significantly by 7.01%. Hybrid approaches combining sliding windows with recent interactions, and extending input sequence lengths to 500 or even 1000 items, delivered the best overall performance. However, these extended approaches had slightly worse perplexity, indicating a trade-off between predictive confidence and actual recommendation performance.

• • •

Unified architectures for search and recommendations

The final theme highlights a growing shift toward unified system architectures that blend search and recommendations, drawing inspiration from foundation models. Instead of deploying multiple single-task models, recent papers present unified frameworks capable of handling diverse retrieval and ranking tasks within a shared infrastructure. For example, LinkedIn’s 360Brew and Netflix’s UniCoRn show how unified models trained on multiple tasks can outperform specialized, single-task counterparts.

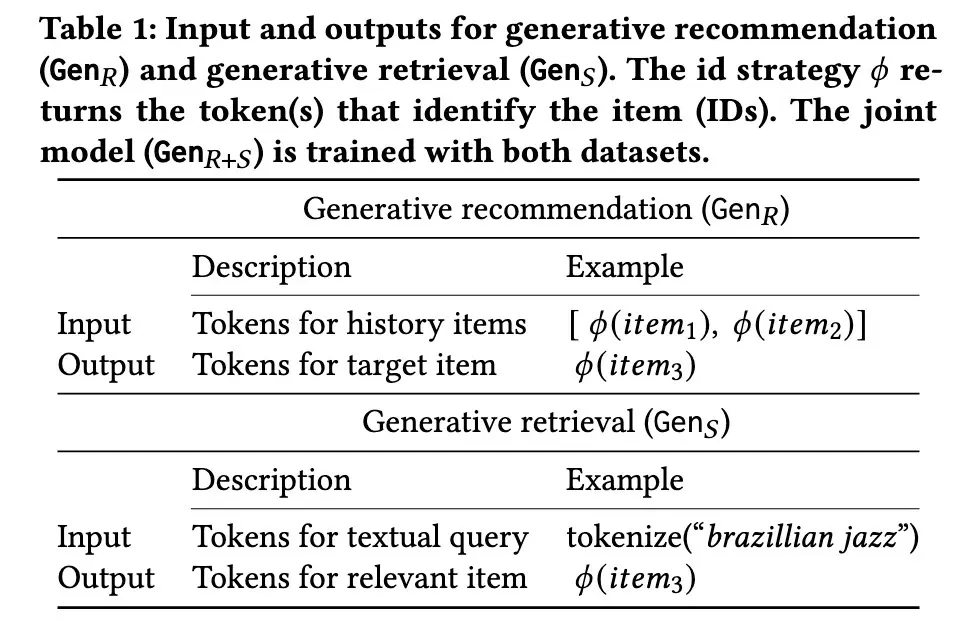

Bridging Search & Recommendations (Spotify) demonstrates the advantages of training a unified generative retrieval model on both search and recommendation data, rather than separately, and how it can outperform task-specific models.

In their approach, a generative recommender predicts item IDs based on a user’s past interactions, while a generative search retriever predicts item IDs from tokenized search queries. The underlying model builds upon Flan-T5-base, extending the vocabulary to include all item IDs with one additional token per item. These models are trained auto-regressively using teacher forcing and cross-entropy loss, aiming to accurately predict the next relevant item ID. During inference, item IDs are generated directly from either a user’s interaction history (for recommendations) or a text query (for search).

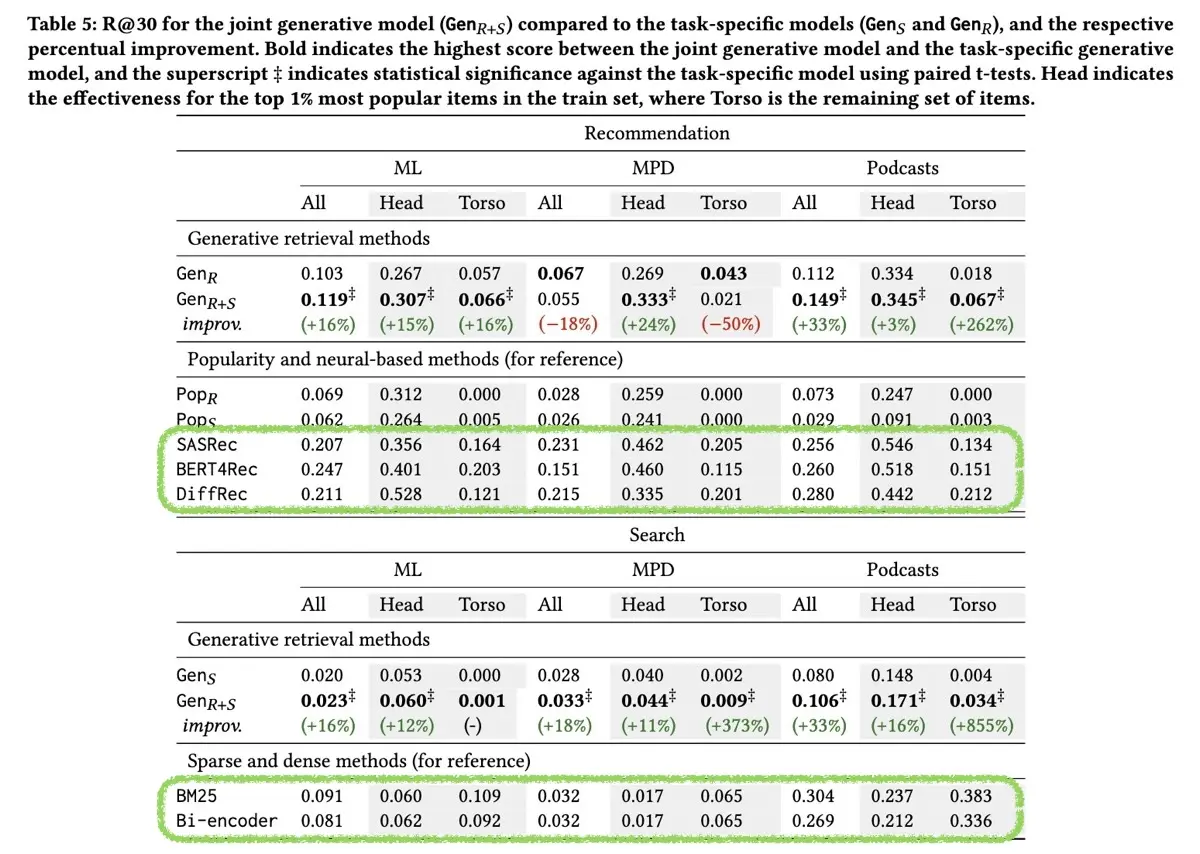

Evaluation is done via standard recall metrics (recall@10 for simulated datasets, recall@30 for real-world datasets) against common baselines like BM25, SASRec, and BERT4Rec.

Results: Jointly trained multi-task models outperformed their single-task counterparts, achieving an average increase of 16% in recall@30. On the Podcasts dataset, the unified model significantly improved performance by +33% across both tasks, especially for torso items (those outside the top 1%), showing gains of 262% for recommendations and 855% for search.

While the research wasn’t focused on replacing conventional models, the comparisons against behavioral baselines were insightful. Across three datasets, generative models consistently lagged behind specialized recommendation baselines (SASRec, BERT4Rec) significantly (green below). Similarly, for search, traditional baselines (BM25, Bi-encoder) were still superior (green below). This indicates that generative retrieval models are still far from fully replacing conventional methods.

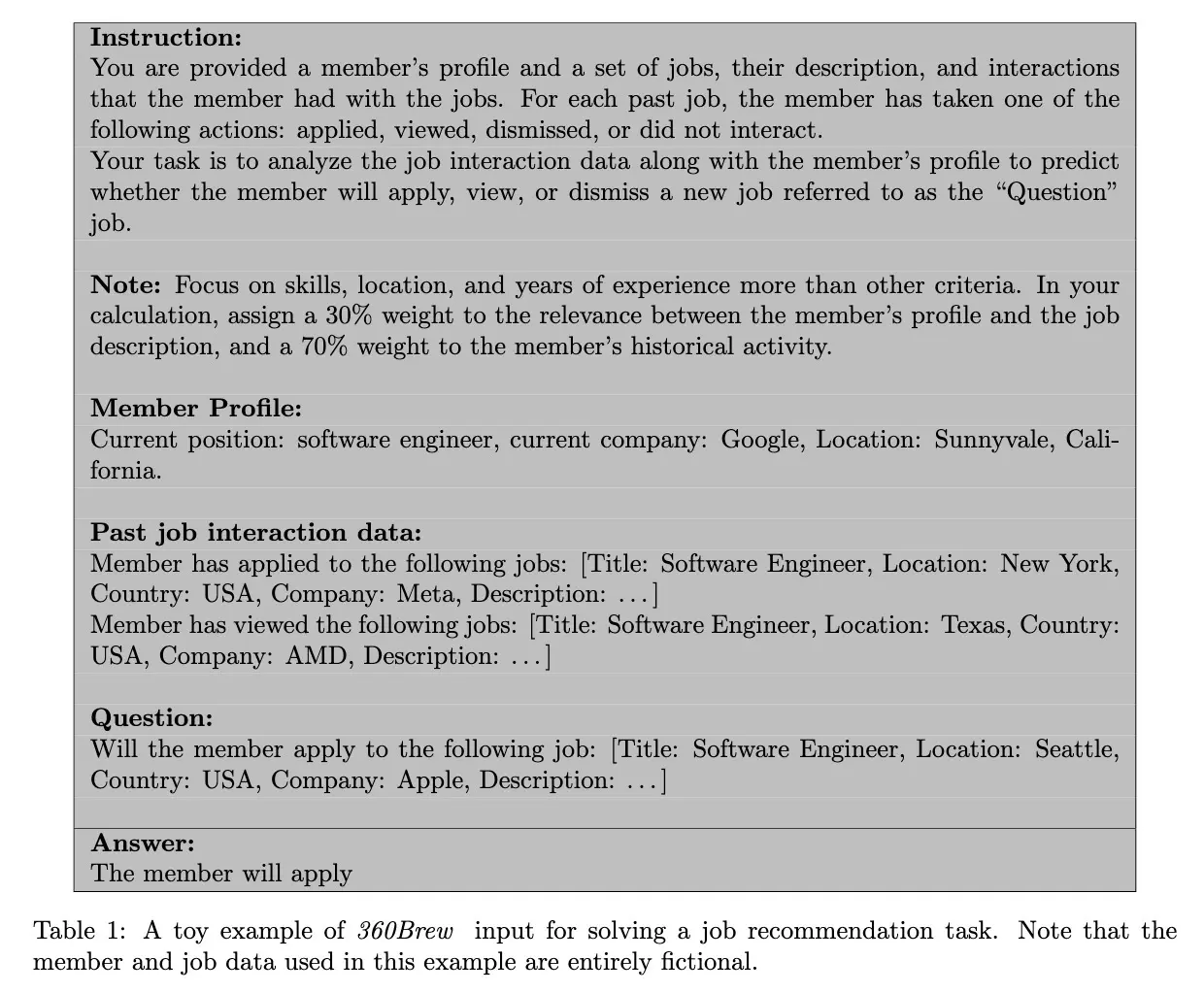

(👉 Recommended read) 360Brew (LinkedIn) consolidates several ID-based ranking models into a single large 150B decoder-only model equipped with a natural language interface, effectively replacing traditional feature engineering with prompt engineering.

360Brew builds upon the Mixtral-8x22B pretrained Mixture-of-Experts model. Its fine-tuning dataset includes 3-6 months of interactions from roughly 45 million monthly active users in the US, encompassing member profiles, job descriptions, posts, and various interaction logs—all transformed into a text-based format.

Training involves three key stages. First, continuous pretraining (CPT) is done with a maximum context length of 16K tokens with packing techniques. Next, instruction fine-tuning (IFT) is performed using a mix of open-source datasets (such as UltraChat) and internally generated instruction-following data. Finally, supervised fine-tuning (SFT) applies multi-turn chat templates designed to enhance the model’s understanding of member-entity interactions, improving its predictive capabilities across specific user interfaces.

The model was trained on 256-512 H100 GPUs using FSDP, and production deployment adopts vLLM and inference-time RoPE scaling. 360Brew focuses on binary prediction tasks, such as whether a user will like a posts, and uses token logits to assign scores.

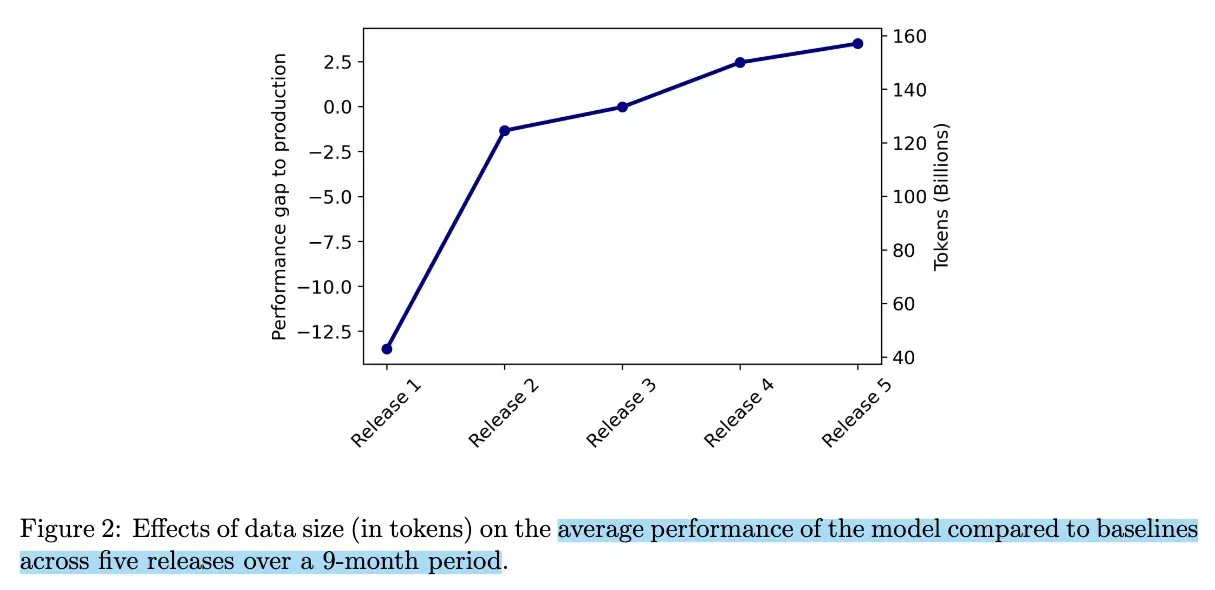

Results: The unified model supports over 30 different ranking tasks across LinkedIn’s platforms, matching or surpassing specialized production models while reducing complexity and maintenance overhead. The researchers also found that the unified model improved substantially with more data—while initial iterations performed poorly, tripling the dataset resulted in performance exceeding specialized models (Figure 2 below). Additionally, larger models consistently outperformed smaller versions (8x22B > 8x7B > 7B). Also, 360Brew delivered strong performance for cold-start users, outperforming traditional models by a wider margin when user interaction data was limited.

Similarly, UniCoRn (Netflix) introduces a unified contextual ranker designed to serve both search and recommendation tasks through a shared contextual framework. This unified model achieves comparable or better performance than multiple specialized models, thus reducing operational complexity.

The UniCoRn model uses contextual information such as user ID, search queries, country, source entity ID, and task type, predicting the probability of positive engagement with a target entity (e.g., a movie). Since not all contexts are always available, heuristics are used to impute missing data. For example, missing source entity IDs in search tasks are imputed as null, and missing query contexts in recommendation tasks use the entity’s display names.

UniCoRn incorporates two broad feature categories: context-specific features (like query length and source entity embeddings) and combined context-target features (such as click counts for a target entity in response to a query). The architecture includes embedding layers for categorical features, enhanced with residual connections and feature crossing.

Training uses binary cross-entropy loss and the Adam optimizer. Netflix incrementally increased personalization: starting from a semi-personalized model using user clusters, progressing to including outputs from other recommendation models, and finally incorporating pretrained and fine-tuned user and item embeddings.

Results: UniCoRn consistently matched or exceeded specialized models. Personalization boosted outcomes, delivering a 10% improvement in recommendations and a 7% lift in search. Ablation studies showed the importance of explicitly including the task type as context, imputing missing features to maximize feature coverage, and applying feature crossing to enhance multi-task learning effectiveness.

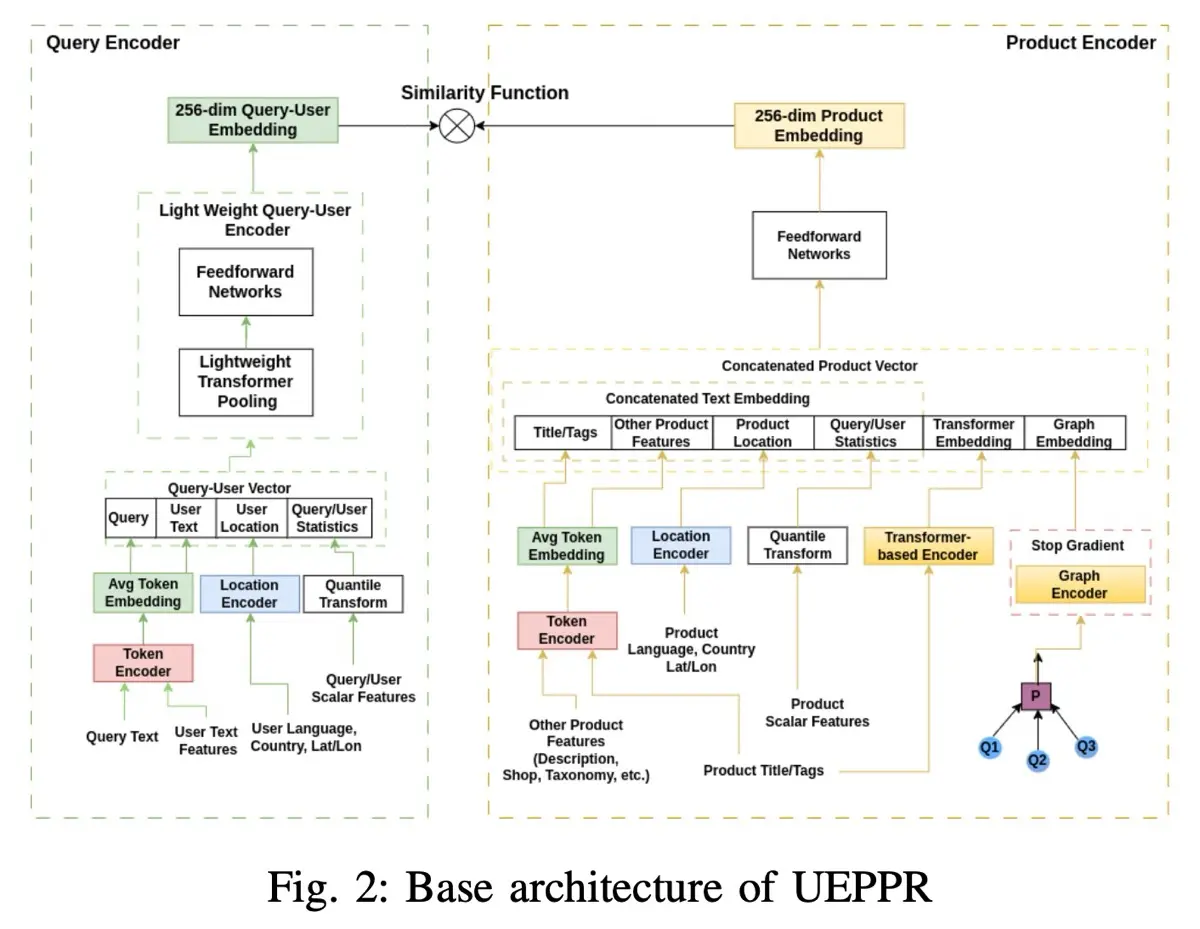

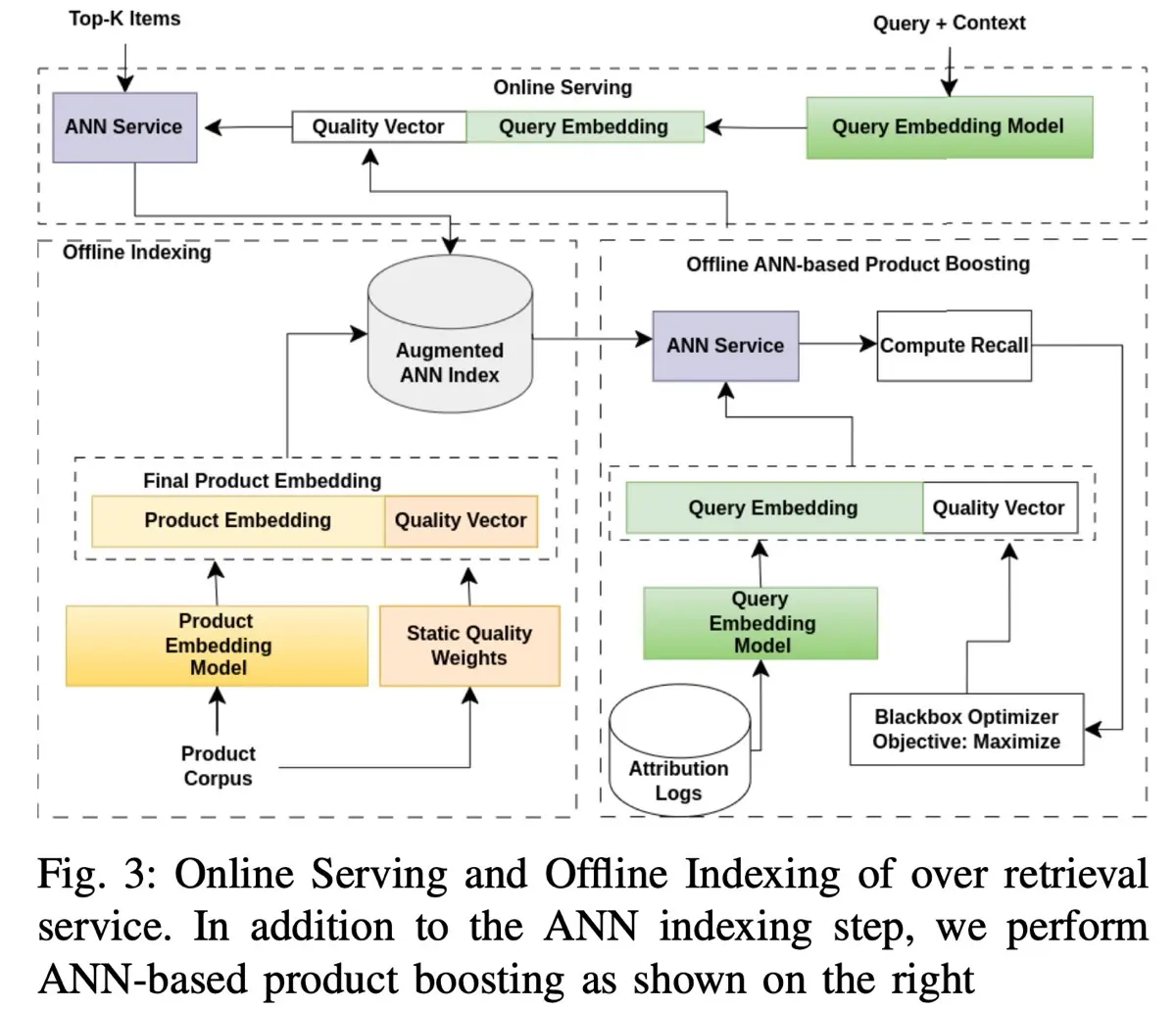

(👉 Recommended read) Unified Embeddings (Etsy) shares how they unified transformer-based, term-based, and graph-based embeddings within a two-tower model architecture. This goal was to address common gaps such as mismatches between search queries and product vocabulary (lexical matching) and the poor performance of neural embeddings due to limited user context.

Their model adopts a classic two-tower structure, consisting of a product encoder and a joint query-user encoder. The product encoder combines transformer-based embeddings, bipartite graph embeddings (trained using a full year of query-product interaction data), product title embeddings, and location information. Interestingly, direct finetuning of transformer-based models like distilBERT and T5 did not yield significant offline metric improvements. Instead, inspired by docT5query, they pretrained a T5-small model specifically designed to predict historically purchased queries based on product descriptions. The query-user encoder combines query text embeddings, location, and historical engagement data. Both query/title and location embeddings are shared across the two towers for consistency.

They emphasize the effectiveness of negative sampling, sharing multiple approaches such as hard in-batch negatives (positives from other queries within the batch), uniform negatives (randomly selected from the entire product corpus), and dynamic hard negatives (random samples narrowed down by the model to identify the most challenging examples). The goal here is to find the most similar negatives to help the model learn on the hardest samples.

To balance relevance with product quality, they integrated quality boosting into their embeddings via an approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) index. Product embeddings are augmented with query-independent quality scores reflecting attributes such as product ratings, freshness, and conversion rates—factors proven to increase engagement independently from query relevance. Given the original product embeddings, they concatenate it with the quality score vectors; the respective query embedding is concatenated with a constant vector. The final score of the product, for a query, is the dot product of the updated product and query embedding.

The system operates through two main stages: offline indexing and online serving. Offline, embeddings and quality scores are generated and pre-indexed into an ANN system (using FAISS with a 4-bit product quantizer). This approach, combined with a re-ranking step, achieves a recall loss below 4% while keeping latency under 20ms@p99. At the online stage, incoming queries are embedded in real time to retrieve products from the ANN index. They also shared how they applied caching while handling in-session personalization features.

Results: In A/B testing, the unified embedding model drove a site-wide conversion lift of 2.63% and boosted organic search purchases by 5.58%. Offline tests showed that Unified Embeddings consistently outperformed traditional baselines for both head and tail queries. Ablation studies revealed the strongest contributions came from graph embeddings (+15% recall@100), followed by description embeddings (+6.3%) and attributes (+3.9%). Additionally, location embeddings significantly improved purchase recall@100 (+8%) for US users by minimizing geographic mismatches. Removing hard negatives resulted in a noticeable 7% drop in performance, underscoring their importance.

Embedding Long Tail (Best Buy) shared how they optimize semantic product search to better address long-tail queries which typically suffer from sparse user interaction data.

To create a high-quality dataset, they collected user engagement data from product pages and applied a two-stage filtering process, reducing data volume (by 10x) while maintaining quality and balanced coverage across product categories. First, they retained interactions observed from at least two unique visitors, then performed stratified sampling across categories to mitigate popularity bias. To further augment this data, they prompted a Llama-13B model to generate ten synthetic search queries per product using the product’s title, category, description, and specifications, thus ensuring comprehensive catalog coverage.

Their model follows a two-tower architecture based on Best Buy’s internally developed BERT variant, an adaptation of RoBERTa finetuned through masked language modeling on search queries and product information. They used the first five layers of this BERT model to initialize both the search and product encoders. Training involved using in-batch negatives with multi-class cross-entropy loss. For deployment, Solr functions as both the inverted index and vector database, with a caching layer added to minimize redundant requests to the embedding service.

Results: Adding semantic retrieval to the existing lexical search improved conversion rates by 3% in online A/B tests. Offline experiments demonstrated incremental improvements through various enhancements: two-stage data filtering (+0.24% recall@200), synthetic positive queries (+0.7%), additional product features (+1.15%), query-to-query followed by query-to-product fine-tuning (+2.44%), and model weight merging (+4.67%). Notably, their final model outperformed the baseline (all-mpnet-base-v2) while using only half the parameters at 50M vs 110M. (Nonetheless, it may not have been a fair comparison given the baseline was not finetuned.)

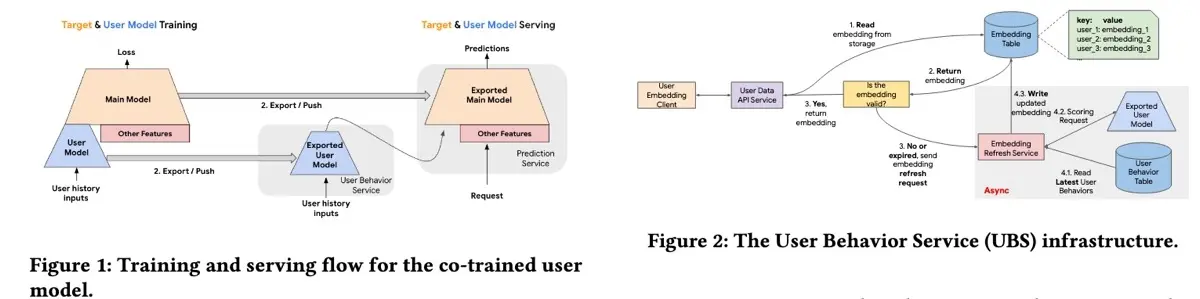

User Behavioral Service (YouTube) presented an innovative approach for serving large user sequence models efficiently while sidestepping latency challenges.

The intuition behind User Behavior Service (UBS) is decoupling the serving of the user sequence model from the main recommendation model. This design allows independent control over user embedding computation. Although both models are co-trained, they are exported and served separately. The user model computes embeddings asynchronously, storing them in a high-speed key-value cache that’s regularly updated. If a requested embedding isn’t available, an empty embedding is returned while an asynchronous refresh is triggered. This setup enables experimentation with significantly larger models without latency constraints—a concept similar to what I described as “Just-in-time infrastructure” in my RecSys 2022 keynote.

Results: In A/B tests, UBS improved performance across six different ranking tasks while limiting the increase in cost. For example, a User Model with a sequence length of 1,000 showed a 0.38% improvement in online metrics compared to a baseline model using a sequence length of 20, with offline accuracy gains ranging from 0.01% to 0.40% across multiple tasks. Directly serving a large user sequence model would have increased costs by 28.7% but the UBS approach limited this increase to just 2.8%.

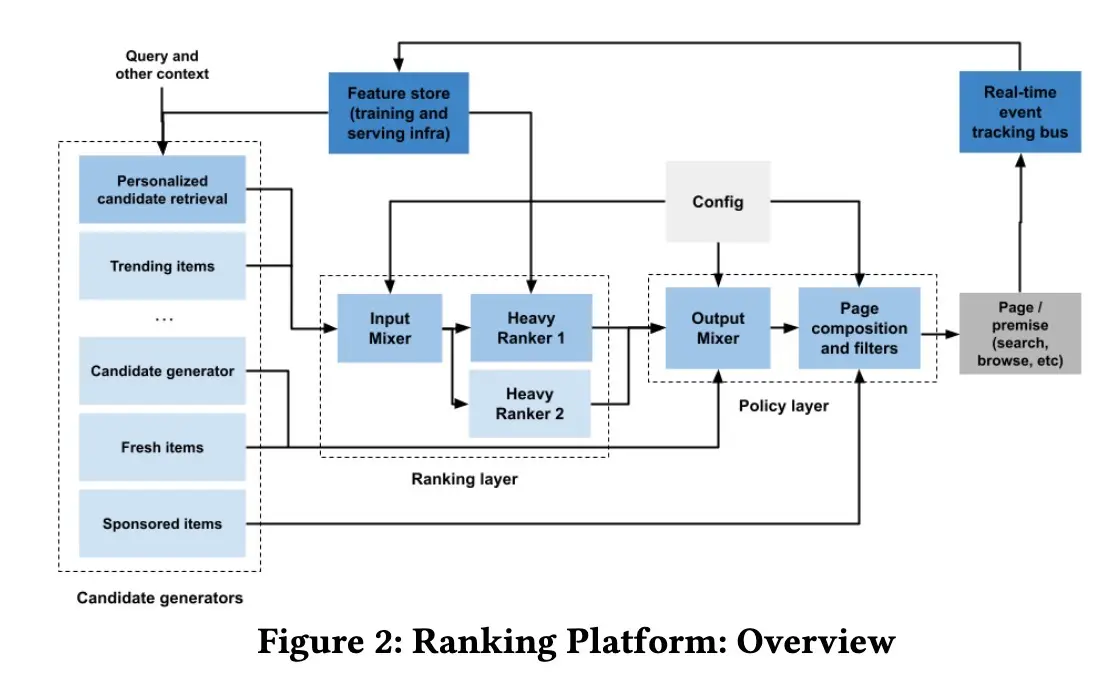

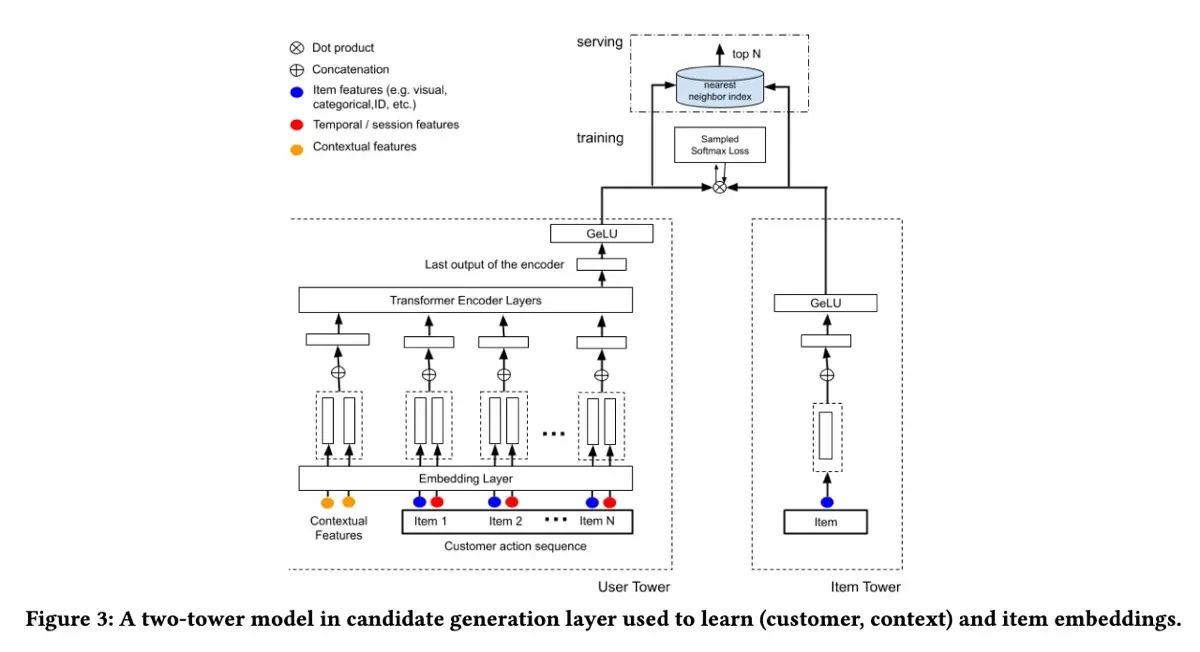

(👉 Recommended read) Modern Ranking Platform (Zalando) details their real-time platform designed for both search and browsing scenarios. The paper discusses their system design, candidate generation, retrieval methods, and ranking policies.

Their platform is built around a few key principles:

- Composability: Models can be combined vertically (layered ranking) or horizontally by integrating outputs from various models or candidate generators.

- Scalability: To manage computational costs, the platform first uses efficient but less precise candidate generators. These initial candidates are then refined by more accurate but computationally intensive rankers, a standard design for recsys.

- Shared Infrastructure: Whenever possible, training datasets, embeddings, feature stores, and serving infrastructure are reused to simplify operations.

- Steerable Ranking: The platform allows external adjustments through a policy layer, making it easy to align rankings with business objectives.

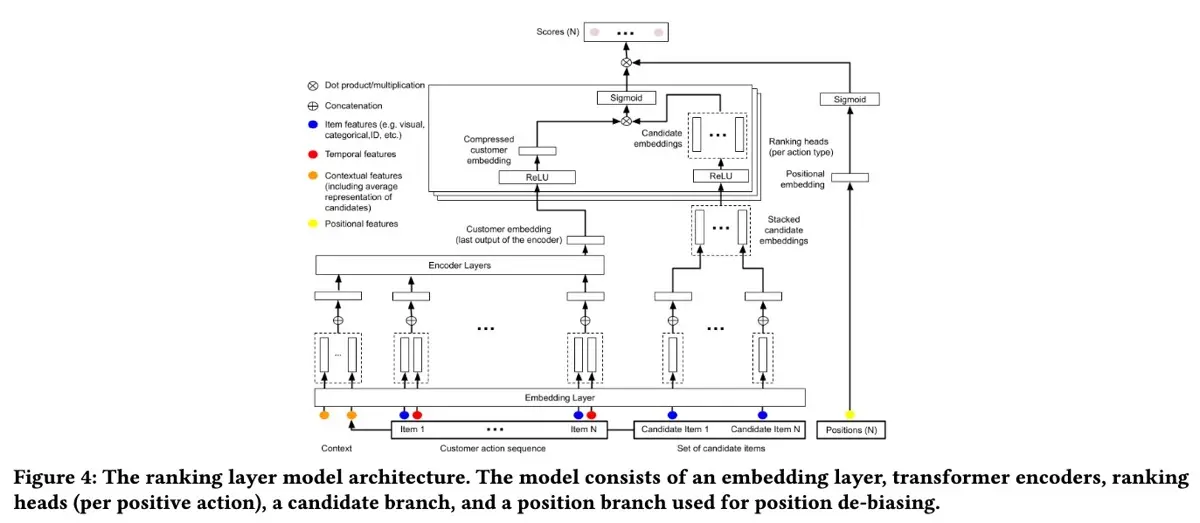

Their candidate generator uses a classic two-tower model. The customer tower updates embeddings based on a customer’s recent actions and current context whenever the customer visits the site, ensuring embeddings remain fresh. The item tower precomputes item embeddings and stores them in a vector database for rapid retrieval. These embeddings are matched via dot product. To create customer embeddings, a Transformer encoder is trained on historical customer behavior and contextual data, predicting the next likely interaction.

The ranker is a multi-task model that predicts the likelihood of different customer actions, such as clicks, adding items to wishlist or cart, and purchases. Each action has its own prediction head, with all contributing equally to training loss. During serving, each action type’s importance can be dynamically adjusted. Overall, the ranker outputs personalized scores for each candidate item across multiple potential customer interactions.

Finally, the policy layer ensures the system aligns with broader business goals. For instance, it can encourage exploration by promoting new products through heuristics like epsilon-greedy strategies. It also applies other business rules, such as reducing the visibility of previously purchased items and ensuring item diversity by preventing items from the same brand from appearing back-to-back.

Results: The unified architecture demonstrated strong performance across four A/B tests, achieving a combined engagement increase of +15% and a revenue uplift of +2.2%. Iterative improvements further illustrate the effectiveness of each system component: introducing trainable embeddings in candidate generation boosted engagement by +4.48% and revenue by +0.18%; adding advanced ranking and policy layers delivered an additional +4.04% engagement and +0.86% revenue; and using contextual data provided a further lift of +2.40% in engagement and +0.60% in revenue.

• • •

Although early research in 2023—that applied LLMs to recommendations and search—often fell short, these recent efforts show more promise, especially since they’re backed by industry results. It suggests that there are tangible benefits from exploring the augmentation of recsys and search systems with LLMs, increasing performance while reducing cost and effort.

References

Chamberlain, Benjamin P., et al. “Tuning Word2vec for Large Scale Recommendation Systems.” Fourteenth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2020, pp. 732–37. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.1145/3383313.3418486.

Hidasi, Balázs, et al. Session-Based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks. arXiv:1511.06939, arXiv, 29 Mar. 2016. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1511.06939.

Chen, Qiwei, et al. Behavior Sequence Transformer for E-Commerce Recommendation in Alibaba. arXiv:1905.06874, arXiv, 15 May 2019. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1905.06874.

Sun, Fei, et al. BERT4Rec: Sequential Recommendation with Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformer. arXiv:1904.06690, arXiv, 21 Aug. 2019. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1904.06690.

Singh, Anima, et al. Better Generalization with Semantic IDs: A Case Study in Ranking for Recommendations. arXiv:2306.08121, arXiv, 30 May 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.08121.

Chen, Gaode, et al. “A Multi-Modal Modeling Framework for Cold-Start Short-Video Recommendation.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 391–400. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688098.

Wang, Hangyu, et al. FLIP: Fine-Grained Alignment between ID-Based Models and Pretrained Language Models for CTR Prediction. arXiv:2310.19453, arXiv, 30 Oct. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.19453.

Vančura, Vojtěch, et al. “beeFormer: Bridging the Gap Between Semantic and Interaction Similarity in Recommender Systems.” 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2024, pp. 1102–07. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3691707.

Li, Yaoyiran, et al. CALRec: Contrastive Alignment of Generative LLMs for Sequential Recommendation. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.02429.

Zhang, Chiyu, et al. EmbSum: Leveraging the Summarization Capabilities of Large Language Models for Content-Based Recommendations. arXiv:2405.11441, arXiv, 19 Aug. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.11441.

Shah, Jaidev, et al. “Analyzing User Preferences and Quality Improvement on Bing’s WebPage Recommendation Experience with Large Language Models.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 751–54. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688062.

Pei, Yingchi, et al. “Leveraging LLM Generated Labels to Reduce Bad Matches in Job Recommendations.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 796–99. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688043.

Search Query Understanding with LLMs: From Ideation to Production. https://engineeringblog.yelp.com/2025/02/search-query-understanding-with-LLMs.html. Accessed 5 Mar. 2025.

Lindstrom, Henrik, et al. “Encouraging Exploration in Spotify Search through Query Recommendations.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 775–77. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688035.

Aluri, Geetha Sai, et al. “Playlist Search Reinvented: LLMs Behind the Curtain.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 813–15. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688047.

Zhang, Gaowei, et al. Scaling Law of Large Sequential Recommendation Models. arXiv:2311.11351, arXiv, 19 Nov. 2023. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.11351.

Wang, Junting, et al. “A Pre-Trained Sequential Recommendation Framework: Popularity Dynamics for Zero-Shot Transfer.” 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2024, pp. 433–43. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688145.

Liu, Qi, et al. Efficient Transfer Learning Framework for Cross-Domain Click-Through Rate Prediction. arXiv:2408.16238, arXiv, 29 Aug. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.16238.

Khani, Nikhil, et al. Bridging the Gap: Unpacking the Hidden Challenges in Knowledge Distillation for Online Ranking Systems. arXiv:2408.14678, arXiv, 26 Aug. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.14678.

Zhang, Yin, et al. “Self-Auxiliary Distillation for Sample Efficient Learning in Google-Scale Recommenders.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 829–31. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688041.

Cui, Yu, et al. “Distillation Matters: Empowering Sequential Recommenders to Match the Performance of Large Language Model.” 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2024, pp. 507–17. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688118.

Yang, Zhiming, et al. MLoRA: Multi-Domain Low-Rank Adaptive Network for CTR Prediction. arXiv:2408.08913, arXiv, 14 Aug. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.08913.

Hsu, Yi-Ping, et al. “Taming the One-Epoch Phenomenon in Online Recommendation System by Two-Stage Contrastive ID Pre-Training.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 838–40. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688053.

Joshi, Swanand, et al. “Sliding Window Training - Utilizing Historical Recommender Systems Data for Foundation Models.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 835–37. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688051.

Penha, Gustavo, et al. Bridging Search and Recommendation in Generative Retrieval: Does One Task Help the Other? arXiv:2410.16823, arXiv, 22 Oct. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.16823.

Firooz, Hamed, et al. 360Brew: A Decoder-Only Foundation Model for Personalized Ranking and Recommendation. arXiv:2501.16450, arXiv, 27 Jan. 2025. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.16450.

Bhattacharya, Moumita, et al. Joint Modeling of Search and Recommendations Via an Unified Contextual Recommender (UniCoRn). arXiv:2408.10394, arXiv, 19 Aug. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.10394.

Jha, Rishikesh, et al. Unified Embedding Based Personalized Retrieval in Etsy Search. arXiv:2306.04833, arXiv, 25 Sept. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.04833.

Kekuda, Akshay, Yuyang Zhang, and Arun Udayashankar. “Embedding based retrieval for long tail search queries in ecommerce.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems. 2024. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3640457.3688039.

Li, Yuening, et al. “Short-Form Video Needs Long-Term Interests: An Industrial Solution for Serving Large User Sequence Models.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 832–34. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3688030.

Celikik, Marjan, et al. Building a Scalable, Effective, and Steerable Search and Ranking Platform. 1, arXiv:2409.02856, arXiv, 4 Sept. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.02856.

If you found this useful, please cite this write-up as:

Yan, Ziyou. (Mar 2025). Improving Recommendation Systems & Search in the Age of LLMs. eugeneyan.com. https://eugeneyan.com/writing/recsys-llm/.

or

@article{yan2025recsys-llm,

title = {Improving Recommendation Systems & Search in the Age of LLMs},

author = {Yan, Ziyou},

journal = {eugeneyan.com},

year = {2025},

month = {Mar},

url = {https://eugeneyan.com/writing/recsys-llm/}

}Share on:

Browse related tags: [ recsys llm teardown 🔥 ] or

Join 11,800+ readers getting updates on machine learning, RecSys, LLMs, and engineering.