A Practical Guide to Maintaining Machine Learning in Production

In the previous post, we discussed six little-known challenges after deploying machine learning. As a recap, here are the six groups:

- Data: Upstream schema changes contaminate data

- Model: Increased complexity hampers maintainability

- Engineering: Fragmented codebase, configuration, and infra

- The Real World: Bias, feedback loops, and adversaries

- Org Structure: Excessive division of labour slows down iteration

- Customers: Frequent operational requests disrupt work

Previous post: 6 Little-Known Challenges After Deploying ML

This follow-up will share some practices I’ve found useful to maintaining machine learning in production. They are:

- Monitor Training and Serving Data for Contamination

- Monitor Models for Misbehaviour When Retraining

- Simplify Engineering to Reduce Operational Burden

- Useful Practices to Minimize Feedback Loops and Bias

- Structure Teams for Iteration and Innovation

- Crowdsource the Handling of Customer Complaints

With close to 20 suggestions, it can get overwhelming. Fret not, I’ll highlight the top three must-haves and good-to-haves at the end of this post.

We'll go through some practical tools to help with maintaining machine learning in prod.

Monitor Training and Serving Data for Contamination

Validate your incoming data. “Data is the New Oil.” “Garbage in, Garbage Out.” These clichés emphasize that clean input data is essential to your system. Here’s how you can monitor your incoming data, starting with the most basic. These checks identify errors upfront and save hours spent unnecessarily fixing your pipeline or decontaminating your feature store.

Check the incoming files (if you receive data via a CSV/TSV/JSON dump). Don’t assume the file format will be consistent—a manual job could be creating them.

- Is the schema correct? Are all expected columns present?

- Is the format correct? (e.g., can your parse it as CSV?)

- Is the encoding correct? (e.g., is it UTF-8 compliant?)

- Is the data volume reasonable? Is it much larger or smaller than previous dumps?

- If the file is encrypted, was the data tampered with, possibly via a man-in-the-middle attack?

Check the data’s overall distribution.

- How many rows are there? Row counts should not fluctuate from day to day.

- Do columns that should not have nulls, have nulls? Is there a sudden increase (or decrease) in the proportion of null values per column?

- Do primary keys (e.g., customer ID, product ID) have duplicates? (Depending on how you do your joins, having duplicates could blow up the number of rows)

Check the features’ distributions.

- For continuous features, are the minimum and maximum values reasonable? E.g., age shouldn’t be below 0 or above a sensible threshold. Do basic aggregates (e.g., median, mean, interquartile range) seesaw from day to day?

- For categorical features, are the unique values constant? If we expect the unique values of

Male,Female, andUndeclaredfor gender, there shouldn’t be additional values such asmaleorMarried. Also, is the proportion of each value similar? - For timestamp features, is the format the same? Is it still dd-mm-yyyy, or did an American DBA change it to mm-dd-yyyy? Also, are the date ranges reasonable? Most of the time, you shouldn’t have dates from the 18th century or the future.

If you want to get fancy, perform statistical checks

- Are the correlations between your features and targets consistent? A sudden increase suggests a data leak; a gradual decrease suggests a data drift.

- Detect changes with homogeneity tests, ANOVAs, and time series analysis. Is gender distribution the same? Use a chi-squared test to (dis)confirm the null hypothesis. (However, if your data is large, statistical significance can be common.)

Here’s a recent article on how Uber monitors data quality via multi-dimensional time series and principal component analysis.

Check for training-serving skew. It’s often caused by discrepancies between training data and input data during serving, leading to disparity in model performance during training and serving.

When serving, log the input data before and after processing and do some checks.

- Is the serving data similar to training data? If the serving data is more sparse, it could be that the training data is unknowingly enriched (e.g., missing customer demographic information is imputed for daily reports).

- Is the feature processing identical during training and serving? This occurs when different code is using in training (batch) and serving (individual query).

Minimize training-serving skew by training on served features. If you’re logging data and features during serving, consider using them as training data. To clarify, use historical processed features (during serving) to train your model. This ensures your model learns on data it would receive and predict on during serving—no more training-serving skew.

As an extra benefit, you can simplify and shrink your training pipeline. E.g., previous ETL jobs to stitch together clickstreams for training data are no longer needed. Just train on the served features.

Monitor Models for Misbehaviour When Retraining

Prune redundant features periodically. After adding features and finding improved model performance, take the extra time to check if all the features are still important. Excluding these redundant features will simplify your model and reduce data pipeline computation cost, with minimal impact on model performance.

Permutation importance is a cheap way to do this—we simply shuffle each column and assess the change in model performance. An alternative, drop-column importance, iteratively drops each column and retrain and evaluate the model—it’s more expensive as we retrain the model on each iteration, but it’s more accurate.

Validate your model before deploying. This is one of my favourites because of its simplicity and effectiveness. When retraining your model, keep a validation hold-out; this could be the latest seven days of data or more, depending on the sample size required. Retrain on the rest of the data.

For example, in a product ranker, how does the model perform on the validation set based on the usual ranking metrics (e.g., AUC, NDCG, recall@k)? Also, does it perform better than a naive baseline (e.g., sorting product based on yesterday’s sales)?

If the model fails the validation checks above, your pipeline should break and not release the model. Better to have a stale model in production than a misbehaving one. If the model passes the validation check, retrain the model on the whole dataset and release it.

You could get more in-depth by comparing the predictions of the previous and current model. If your previous model ranks a product at 10,000th but your current model ranks it at 1st, something seems off. This can apply to various types of machine learning problems, be it ranking (difference in rank), classification (difference in probability), and regression (difference in numeric prediction).

Shadow release your model. You can do this by running your model in production, running some live traffic through it, and logging the outcomes.

What is the latency, stability, and error rate—this tells us if the model is production-ready (especially important if there was a big change, such as changing the model from decision trees to neural networks). How do the live predictions perform in terms of metrics (e.g., recall, precision)? Are there more false negatives or false positives?

When applied together, the above two practices ensure end-users do not notice model changes unless there is an improvement.

Monitor your model health. As a first step, check for model staleness. When was the last time you refreshed the production model?

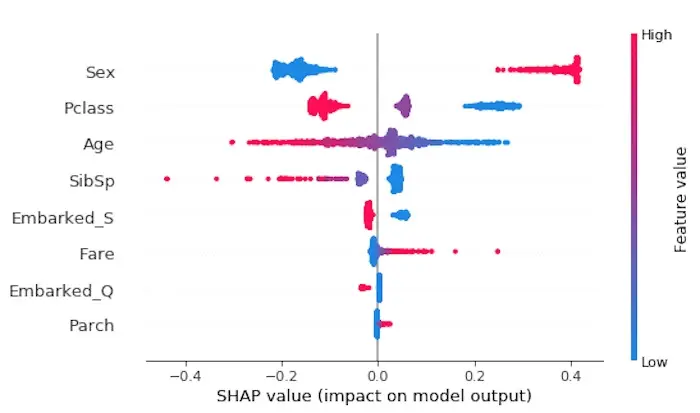

Then, take it further by inspecting the model for bias or incorrect learning. This is easier now with tools for model interpretability such as LIME and SHAP. If it’s a loan approval model, does it bias against certain genders, age groups, or ethnicities? (Though I would argue that, in the first place, such data shouldn’t be considered.) How do the most important features change from day-to-day? If a feature jumps in importance, it could suggest a data leak.

This SHAP summary plot shows sex, passenger class, and age were most important as features.

Meta-analysis on offline vs offline metrics. How well do your offline metrics correlate with online improvements? Does an increase in AUC or NDCG in offline evaluation lead to an increase in click-through rate or conversion rate online?

For example, Etsy found AUC to be a good metric to assess CTR while this KDD paper found large discrepancies between offline and online performance of models due to evaluation metrics.

We make many decisions based on offline evaluation metrics, such as during experimentation and model validation before release. Investing in finding dependable offline metrics will continuously pay dividends.

(An aside: When measuring online performance, focus on what your system can have a direct impact on, such as clicks, purchases, bounce rate. Consider indirect metrics (e.g., user return rate, daily average users) only after you grok the direct metrics. Avoid delayed and big-picture metrics (e.g., user satisfaction, traffic growth)—there could be multiple confounding factors for these.)

Simplify Engineering to Reduce Operational Burden

Log your configuration details. This extends to both experimentation and production workflows. Model hyperparams? Log it. The threshold to convert probabilities to binary? Log it. The period of historical training data used? Log it. Heck, might as well log the commit hash too.

I’ve found MLflow to be a lightweight library for this purpose. With a small amount of additional code, you can log configurations, code commits, and results (e.g., evaluation metrics, graphs, sample CSVs). All accessible in a centralised dashboard. Here’s a previous post on it.

Serve your models via containers. Or VMs, if that’s more of your thing. The intent is to remove variability between training and serving environments. No more “But it runs on my machine…” troubles.

Docker seems to be the de facto container technology now. It enables "build once, run everywhere", and scales well horizontally. Good articles on docker for machine learning deployment here and here.

Build in rollback capability. If, for some reason, a refreshed model passes the above data and model validation checks but misbehaves when deployed, you’ll want to quickly revert. This rollback capability is your insurance policy.

If you’re using Docker containers to serve, this is straightforward—just pick up the previous working container from the repository and deploy it to replace the faulty model. Keep working images from previous deployments in your repository, seven or more if resources permit.

This ensures you immediately fix the problem for customers. Once the pressure is off, you’ll be able to better focus on digging into the root cause and resolving it.

Make a conscious effort to keep things simple. Start simple. Keep your system simple as long as possible. Complexity will creep in—beat it back. Here’s how one successful start-up did it:

When Instagram was acquired in 2012, it had a 13-person team serving tens of millions of users. It scaled and kept operational burden per engineer low by sticking to proven technologies instead of new, shiny ones. When other startups adopted trendy NoSQL data stores and struggled, Instagram kept it lean with battle-proven and easy to understand PostgreSQL and Redis.

For machine learning systems, start with simple, interpretable models, minimal features, and no ensembling. Have model refreshes at a bearable cadence (e.g., weekly or daily) and don’t spring for real-time updates right off the bat. Start with a general model that works for most users before moving to personalisation.

Useful Practices to Minimize Feedback Loops and Bias

Use positional features to avoid feedback loops. This neat trick reduces much of the bias where a user’s interactions depend on the item’s rank.

In ranking or recommendation, the position of the item (e.g., product, advertisement) affects how likely users will click on it. A higher ranked item is naturally clicked more. How do you control for this real-world bias in the training data?

By including positional features. During training, the model will learn to weigh these features highly, given the high correlation with CTR. Then, during serving, when determining the item rank, you can drop these positional features or set it to a constant.

Learn thresholds from data. Fixed thresholds for binarizing probabilities can be tricky to maintain and vulnerable to data drift. Instead, consider learning it with each model refresh.

For example, what are your production requirements? Do you need 95% recall? Or minimal false positives? Or a good balance? Evaluate which thresholds (e.g., in Python, [x/100 for x in range(1, 100, 1)]) meets those requirements and use it in production.

Audit a sample of your data periodically. Monthly or weekly is good. This is especially important the next set of training data includes these predictions. If your predictions have many errors, and are then used as training data, this could lead to a vicious cycle.

For example, if you’re classifying product reviews daily for spam, offensive language, and personal details, erroneous predictions go on to become the next set of (incorrect) training data.

What you’ll want to do is take a small sample of reviews (e.g., 1% - 5%) and have people go through them. Are there obvious errors or new types of fraud emerging? Is there a general pattern to them? Once you find these error patterns, you can get the misclassified reviews via logic or regex to relabel them. Then, you can relabel other misclassifications via active learning.

Structure Teams for Iteration and Innovation

Have your data scientists do end-to-end. I’ll admit, this is not a popular opinion as most tech teams move toward division of labour. But, hear me out.

A generalist (or if you prefer, full-stack) data scientist can perform diverse functions: communicate with stakeholders to define the right problem, develop prototypes and production code, and deploy and measure. This increases learning, innovation, and iteration speed. It also encourages individual ownership and reduces diffusion of responsibility.

Netflix has full-cycle developers and it worked well. Stitch Fix starts with a full-stack data scientist model and only specialise when necessary.

Caveat: This practice assumes good tooling and infrastructure support. Spark instances should be easy to spin up, automatic failover and rollback should be in place, and A/B tests should be simple to start. With these, your generalist data scientists can focus on machine learning system development.

If you cannot have end-to-end data scientists, have end-to-end teams. I get it, end-to-end data scientists are rare (though I would argue they’re not unicorns; you can find as well as make them). If so, build end-to-end teams instead.

Have your PM, data scientists, and engineers sit together (after this pandemic blows over). Ensure teams align the same goals of fast iteration and shipping. Have processes that minimize coordination and communication costs (i.e., have quick, informal discussions instead of scheduling meetings).

Define clear interfaces between each role. If different teams own different parts of the machine learning process, ensure that people don’t just “throw code over the wall”. Set clear expectations and interfaces for deliverables.

For example, the deliverable for data engineers could be timely updates in the database—this is the input interface for data scientists. The data scientists then build their machine learning models and deliver a docker container with a model.predict() API—this is their output interface.

Crowdsource the Handling of Customer Complaints

Make it easy for others to take action. This includes customer service agents, account managers, and policymakers. You can accomplish this via simple user interfaces (UI) to input product and customer IDs; these are then stored in a database.

Are customers complaining about inappropriate products in recommendations or search results? Let agents blacklist the product ID via the UI. Does a customer have privacy concerns? Again, add their ID via the UI. Does an account manager want to increase a new product’s visibility? Add the product ID via the UI to give it a temporary boost (this helps with cold-start products too). Or better yet, build a new ad business and crowdsource boosting to sellers.

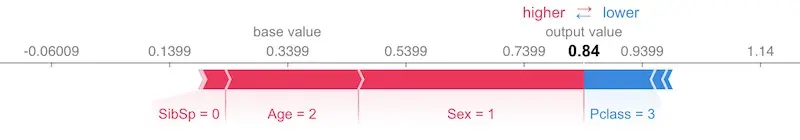

Help operations staff understand model outputs.When machine-learning decisions have repercussions, people will want an explanation. Help your frontline agents understand and explain decisions to customers. I’ve found SHAP force plots useful for this. LIME is also a good alternative.

Here’s an example where we predict passenger survivability from the famous Titanic dataset. For this passenger, we see that gender and age had a big positive influence on survivability—after all, women and children first. Her having a 3rd class cabin had a negative impact—lower class cabins are in the lower decks and thus further away from the lifeboats.

This SHAP force plot shows being female and low in age improved survivability.

Some (Important) Practices I Didn’t Discuss

There were a few key points I skipped. They’ve been well covered in other resources; nonetheless, I thought I should briefly mention them here.

- Standard engineering practices: This include code reviews, your test suite (i.e., unit test, integration test, infra tests), and proper documentation. I would extend this to include methodology reviews too. Is the SQL logic correct? Was the train-validation split done properly (without data leaks)?

- A/B (and bandit) testing: They are de facto for releasing online products and features. Don’t skip it (unless you know what you’re doing).

- Notification fatigue: (I didn’t quite know where to fit this.) With proper monitoring, your team could start to get a lot of alerts. Too many alerts and they’ll ignore them, defeating the purpose. Tweak the precision-recall trade-off—prioritise alerts that are high precision and value (i.e., critical impact on customer experience).

That’s a Lot; How should We Prioritise?

I didn’t plan for this post to be so overwhelming. Let me conclude with the top three must-haves and good-to-haves here (disclaimer: my start-up experience influenced these and they’re likely subjective).

IMHO, these are must-haves in most teams:

- Model validation before deployment: This is my favourite practice. With a single check, you eliminate most machine learning misbehaviour before deployment.

- Input data validation: Basic checks go long way—the number of rows, presence of erroneous duplicate values, proportion of null values. Then, check the ranges of numeric and date columns as well as the unique values of categorical columns.

- Easy rollback: This insurance policy lets your team iterate and deploy fast, paving the way for CI/CD. A deployment broke

prodin the middle of the night? No worries, rollback and fix it tomorrow morning.

Next, here are three good-to-haves:

- Have your data scientists do end-to-end: In my experience, this greatly reduces time for development, accelerates learning and innovation, and cultivates a culture of ownership.

- Invest in data science tooling: Have template

Dockercontainers to develop and deploy machine learning models in. Set up a centralisedMLflowserver to share and review results.Airflowis great for scheduling jobs with dependencies. - Invest in customer service tooling: Build tools to empower customer service agents on the most common tasks (e.g., blacklisting products, explaining outcomes). This reduces the amount of ad hoc requests and fire fighting your team handles.

References

Thanks to Yang Xinyi, Marianne Tan, and Stew Fortier for reading drafts of this.

If you found this useful, please cite this write-up as:

Yan, Ziyou. (May 2020). A Practical Guide to Maintaining Machine Learning in Production. eugeneyan.com. https://eugeneyan.com/writing/practical-guide-to-maintaining-machine-learning/.

or

@article{yan2020maintain,

title = {A Practical Guide to Maintaining Machine Learning in Production},

author = {Yan, Ziyou},

journal = {eugeneyan.com},

year = {2020},

month = {May},

url = {https://eugeneyan.com/writing/practical-guide-to-maintaining-machine-learning/}

}Share on:

Browse related tags: [ machinelearning engineering production ] or

Join 11,800+ readers getting updates on machine learning, RecSys, LLMs, and engineering.