Simplicity is An Advantage but Sadly Complexity Sells Better

We sometimes hear of a paper submission being rejected because the method was too simple, or a promotion being denied because the work artifacts lacked complexity. I think this can be partly explained by Dijkstra’s quote:

“Simplicity is a great virtue but it requires hard work to achieve it and education to appreciate it. And to make matters worse: complexity sells better.” — Edsger Dijkstra

Why does complexity sell better?

Complexity signals effort. Papers with difficult ideas and technical details suggest blood, sweat, and tears. Systems with more components and features hint at more effort than systems with less. Because complex artifacts are viewed as requiring more effort, they’re also deemed as more challenging to create and thus more worthy. And because of the perceived effort involved, they’re often judged to be higher quality.

Complexity signals mastery. A complex system with many moving parts suggests that the designer has proficiency over each part and the ability to integrate them. Inaccessible papers peppered with jargon and proofs demonstrate expertise on the subject. (This is also why we quiz interview candidates on algorithms and data structures that are rarely used at work.) If laymen have a hard time understanding the complex idea or system, its creator must be an expert, right?

Complexity signals innovation. Papers that invent entirely new model architectures are recognized as more novel relative to papers that adapt existing networks. Systems with components built from scratch are considered more inventive than systems that reuse existing parts. Work that just builds on or reuses existing work isn’t that innovative.

“The idea is too simple, almost like a trick. It only changes one thing and everything else is the same as prior work.” — Reviewer 2

Complexity signals more features. Systems with components that can be mixed and matched suggest flexibility to cover all the bases. For example, supporting both SQL and NoSQL data stores, or enabling both batch and streaming pipelines. Because complex systems have more lego blocks relative to simple systems, they’re considered more adaptable and better able to respond to change.

All in all, the above leads to complexity bias where we give undue credit to and favour complex ideas and systems over simpler ones.

Why is simplicity an advantage?

Simple ideas and features are easier to understand and use. This makes them more likely to gain adoption and create impact. They’re also easier to communicate and get feedback on. In contrast, complex systems are harder to explain and manage, making it difficult for users to figure out what to do and how to do it. Because there are too many knobs, mistakes are more frequent. Because there are too many steps, inefficiency occurs.

Simple systems are easier to build and scale. Systems that require less rather than more components are easier to implement. Using standard, off-the-shelf technology also makes it easier to find qualified people who can implement and maintain it. And because simpler systems have less complexity, code, and intra-system interactions, they’re easier to understand and test. In contrast, needlessly complex systems require more time and resources to build, leading to inefficiency and waste.

When Instagram was acquired in 2012, it had a 13-person team serving tens of millions of users. It scaled and kept operational burden per engineer low by sticking to proven technologies instead of new, shiny ones. When other startups adopted trendy NoSQL data stores and struggled, Instagram kept it lean with battle-proven and easy-to-understand PostgreSQL and Redis.

Simple systems have lower operational costs. Deploying a system is not the finish line; it’s the starting line. The bulk of the effort comes after the system is in production, likely by someone other than the original team that built it. By keeping systems simple, we lower their maintenance cost and increase their longevity.

Simple systems have fewer moving parts that can break, making them more reliable and easier to fix. It’s also easier to upgrade or swap out individual components because there are fewer interactions within the system. In contrast, complex systems are more fragile and costly to maintain because there are so many components that need to be grokked by a limited team. Having more interdependent parts also makes troubleshooting harder.

“The more simple any thing is, the less liable it is to be disordered, and the easier repaired when disordered.” — Thomas Paine, Common Sense, 1776

Specific to machine learning, simple techniques don’t necessarily perform worse than more sophisticated ones. A non-exhaustive list of examples include:

- Tree-based models > deep neural networks on 45 mid-sized tabular datasets

- Greedy algorithms > graph neural networks on combinatorial graph problems

- Simple averaging ≥ complex optimizers on multi-task learning problems

- Simple methods > complex methods in forecasting accuracy across 32 papers

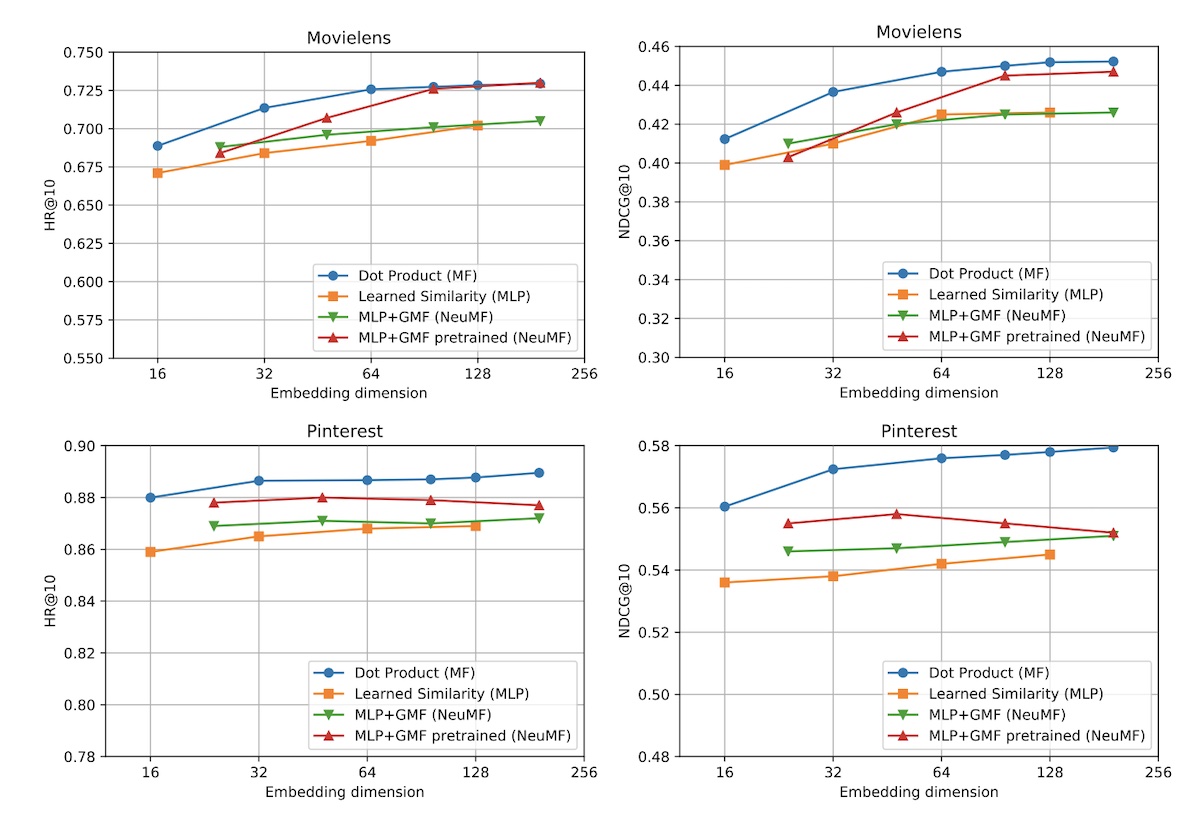

- Dot product > neural collaborative filtering in item recommendation and retrieval

The humble dot product outperforms deep learning methods for recommendations (source)

What’s wrong with rewarding complexity?

It incentivizes people to make things unnecessarily complicated. Using simple methods or building simple systems may appear easier and is thus valued less. As a result, people game the system to get more rewards and the simplest solution is no longer the most obvious one. Complexity begets more complexity, eventually making it impossible to work.

It also encourages the “not invented here” mindset where people prefer to build from scratch and shun reusing existing components even though it saves time and effort. This wastes time and resources and often leads to poorer outcomes.

Unfortunately, most promotion processes overemphasize complexity in work artifacts.

Simple solutions are easier to implement and scale than complex solutions. However promotions often are rewarded to those who create complex solutions. We need to start acknowledging the power of simple. Don’t accept complex. It’s a trap.

— Bryan Liles (@bryanl) August 5, 2022

Ditto for machine learning paper submissions.

A common point raised by ML reviewers is that a method is too simple or is made of existing parts. But simplicity is a strength, not a weakness. People are much more likely to adopt simple methods, and simple ones are also typically more interpretable and intuitive. 1/2

— Micah Goldblum (@micahgoldblum) August 2, 2022

(If your idea didn’t get the credit it deserves, take comfort in the fact that breakthroughs such as Kalman Filters, PageRank, SVM, LSTM, Word2Vec, Dropout, etc got rejected too. We’re generally bad at assessing how useful or impactful an innovation will be. 🤷)

How should we think about complexity instead?

The objective should be to solve complex problems with as simple a solution as possible. Instead of focusing on the complexity of the solution, we should focus on the complexity of the problem. A simple solution demonstrates deep insight into the problem and the ability to avoid more convoluted and costly solutions. Often, the best solution is the simple one.

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler” — Albert Einstein

Instead of having a complex, catch-all solution, consider multiple focused solutions. A one-size-fits-all solution is usually less flexible and reusable than expected. And because it serves multiple use cases and stakeholders, it tends to be “tightly coupled” and require more coordination during planning and migrations. In contrast, it’s easier to operate—and unavoidably, deprecate—single-purpose systems.

In my many years as tech lead, later as consultant and then in @godotengine, I believe the biggest enemy software engineers fight is the deep & common belief that one-size-fits-all solutions to problems (even hypothetical) always exist. Accepting they don't leads to better code. pic.twitter.com/Tc14NGOexi

— Juan Linietsky (@reduzio) July 3, 2022

Is the juice worth the squeeze?

One way to overcome the complexity bias is Occam’s razor. It states that the simplest solution or explanation is usually the right one. Thus, let’s not be too quick to dismiss simple ideas or add unnecessary complexity to justify their worth.

Alternatively, ask yourself: Given the cost of complexity, is the juice worth the squeeze?

Thanks to Yang Xinyi and Swyx for reading drafts of this.

Addendum: Rasmus on the flip side, where people prefer familiar—but more complex components—thus wasting resources & leading to worse outcomes.

I love this article, thank you so much for writing this! 🤩

There is only one thing here I’d like to discuss and elaborate on for a bit:

It [rewarding complexity] also encourages the “not invented here” mindset where people prefer to build from scratch and shun reusing existing components even though it saves time and effort. This wastes time and resources and often leads to poorer outcomes.

I don’t feel like this is quite nuanced enough, and I believe there is more to discuss here.

In my experience, the “not invented here” mindset has an equally powerful opposite bias, where people automatically prefer to reuse existing components because they already know them, it’s easier relative to their individual experience, and it saves their time and effort - however, if those existing components are very complex, this can end up wasting time and resources and leading to poorer outcomes as compared to building something simpler.

If we want to emphasize simplicity, when no simple option is available, sometimes we have to invent something new.

And don’t get me wrong, I’m not ignorant of the fact that this often goes wrong - we often think something could be simpler, and we end up building something that’s only different but just as complex as the thing we were trying to simplify. Some problems are inherently complex, requiring essential complexity that we can’t actually get rid of in practice.

My favorite “bad” example is ORMs - we keep building more, they all start out simple, and then explode in complexity. The object/relational impedance mismatch is a well documented fact, and the idea itself is inherently complex. (and if you’re thinking of an ORM right now that managed to stay simple, it’s probably not an ORM, and more likely just a query builder or data mapper, etc.)

By contrast, a “good/bad” example is how the PSR-6 cache API was followed by the much simpler PSR-16 cache API, which reduced the complexity and number of concepts, making the API much smaller and less opinionated - you can write a PSR-6 adapter for a PSR-16 implementation (and, for that matter, vice-versa) demonstrating the fact that none of the complexity that was removed by PSR-16 was essential to begin with.

There are many libraries and frameworks out there that go far beyond dealing with essential complexity - they often do so in the name of “developer experience”, a rather lofty idea, and aptly named “developer” rather than “development”, highlighting the fact that this value is often completely subjective and relative to individual experience; as opposed to real simplicity, which is an objective and measurable thing. (lines of code, number of public methods, amount of coupling, etc.)

These libraries can sometimes grow to 10x their original size over the cause of a few years - often with major breaking changes every 6-12 months and, ironically, this is perceived as “good” as well, but often indicates a complete failure to keep the scope of a package contained, focused, and small. In fact, libraries that don’t exhibit growth are often perceived as being “dead”, and people are often motivated to move on to packages that are more “active”, another clear symptom of complexity bias.

Sometimes we have to build something new to avoid this sprawling complexity - if we can make things truly simpler, if we can bolt down the requirements and avoid sprawling growth, this can be a good thing, and sometimes it’s the only way to control the infectious complexity we often inherit from “over active” libraries and frameworks.

It’s a nuanced topic and we need to be careful not to feed either of these opposing biases. 🙂

If you found this useful, please cite this write-up as:

Yan, Ziyou. (Aug 2022). Simplicity is An Advantage but Sadly Complexity Sells Better. eugeneyan.com. https://eugeneyan.com/writing/simplicity/.

or

@article{yan2022simplicity,

title = {Simplicity is An Advantage but Sadly Complexity Sells Better},

author = {Yan, Ziyou},

journal = {eugeneyan.com},

year = {2022},

month = {Aug},

url = {https://eugeneyan.com/writing/simplicity/}

}Share on:

Browse related tags: [ machinelearning engineering production 🔥 ]

Join 9,300+ readers getting updates on machine learning, RecSys, LLMs, and engineering.